The year is 1630, and a bearded man in dark clothing sits aboard the Arbella, a vessel bound for the shores of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He is studiously penning a sermon which he has entitled “A Model of Christian Charity”. This man and his sermon will go on to define the United States as we know it today, shaping the very soul of the nation for centuries to come. The author, however, will go on to fade into relative obscurity.

His name is John Winthrop. And he is America’s forgotten founding father.

This is an excerpt from his sermon.

“We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when He shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations, "may the Lord make it like that of New England." For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.”

The “City Upon a Hill” section of Winthrop’s speech is familiar to most Americans—it was famously quoted by John F. Kennedy in 1961, and again by Ronald Reagan in 1980, and was continually alluded to, in various ways, by American presidents thereafter.

This founding image of America as a shining example, as a lighthouse for a world wracked by storm, is deeply embedded into the American psyche. It gave rise to American exceptionalism—the belief that America is inherently different from other nations, and that it has a unique mission to transform the world. It is a mindset that can be seen at work throughout American history, including through today.

But who was this man who founded not only the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but also the soul of a nation?

The Puritan

John Winthrop was born in 1588, the same year that the British Royal Navy devastated the Spanish Armada, effectively ending the reign of Catholic Spain and raising Protestant Britain up as the ruling European power.

Winthrop grew up in prosperous times as the son of a well-to-do land owner, and as a young man, he began to feel that England was in spiritual trouble—its inhabitants were pursuing wealth at the cost of their holiness, the church was corrupt, and Puritans, like the intensely religious Winthrop, were being persecuted.

The Puritans—who called themselves “the Godly” at the time—were a group of religious reformers who intended to “purify” the Church of England of its Catholic practices.

One of the biggest differences between Puritans and the Church of England was that Puritans believed that everyone should be literate and able to read scripture for themselves. The Church of England used intermediaries, usually priests, between man and God.

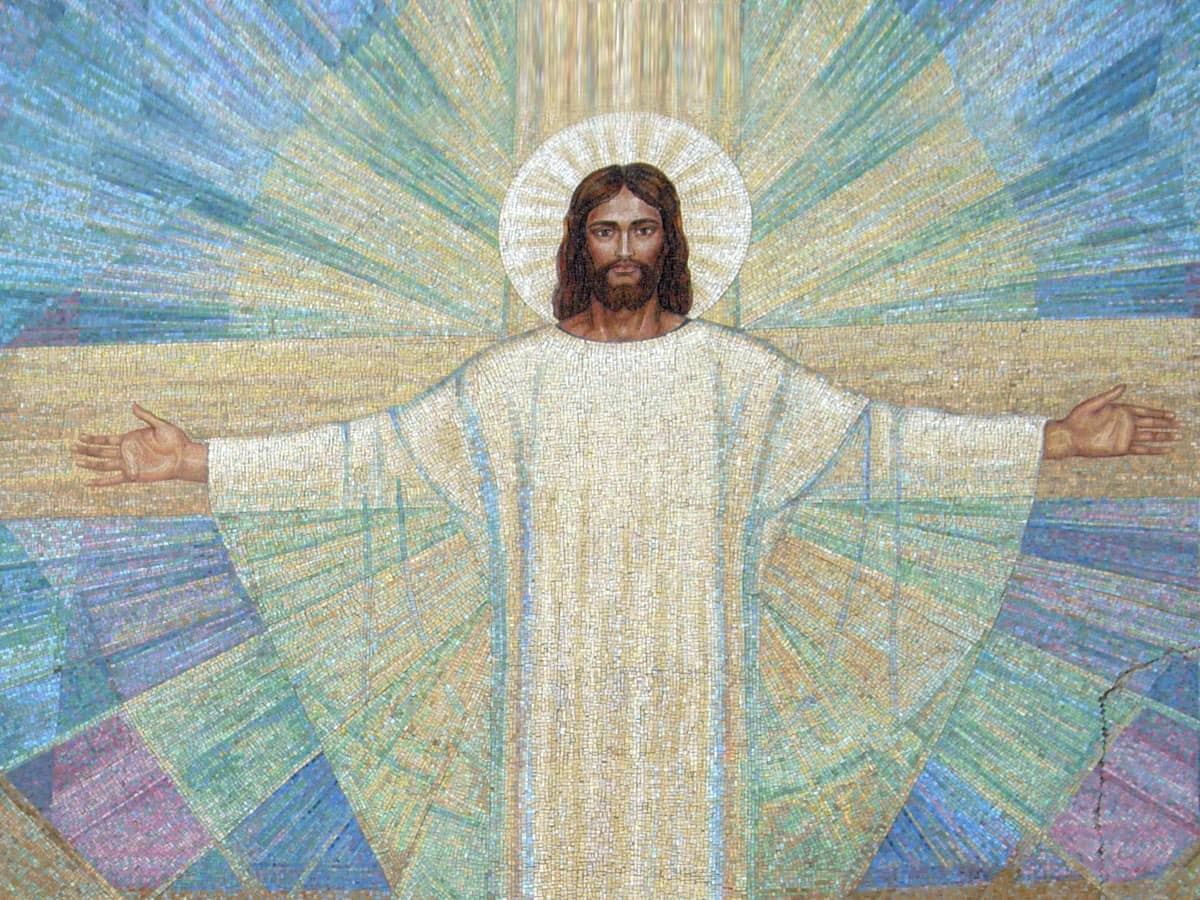

Puritans also felt that the Church of England was far too ostentatious. The rich decorations, art, elaborate ceremonies, and music were all distractions that the Puritans felt encouraged materialism and worldliness.

But the Puritans were violently blocked from changing the Church of England from within, and were increasingly restricted by English law controlling the practice of religion. Because of all this, they sought to establish new religious settlements elsewhere where they could practice their own vision of Christianity in peace.

And in 1629, John Winthrop, now an attorney, agreed to lead them to America.

The Governor

On April 8th of 1630, 11 ships left the English Isle of Wight, carrying Winthrop, around a thousand Puritans, and provisions for all. It was during this voyage that Winthrop wrote and presented his all-important “A Model of Christian Charity”.

Soon after landing in Salem, then-governor John Endicott handed over the governance of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to Winthrop.

From this point on, Winthrop was the shaping force of the colony, and despite an initially difficult winter that took the lives of over 200 colonists, he successfully laid the foundations for a flourishing colony. He had begun to create his “City on a Hill," quickly becoming a father figure for the burgeoning colony.

Much of the success of the colony rested on Winthrop’s temperate attitude—he understood that some disagreement amongst the colonists was inevitable, especially in religious matters. His inclination toward compromise helped to maintain social order in the colony.

But his influence didn’t stop there. Because of Winthrop’s Puritan belief in literacy, the Massachusetts Bay Colony enjoyed unprecedented educational opportunities, and because of his religious belief in the sanctity of discipline and hard work, the colony had no shortage of helping hands. In fact, Winthrop’s idea that everything a person does, including business, is to be done for God, and to the best of one’s ability, largely created what we know as the modern American work ethic.

Winthrop would go on to be elected governor several times between the years 1630 and 1648, each time striving toward what he saw as a better world, and a better way of life—one radically different than that of England’s. But even with this grand vision with its radical goal, Winthrop worked within traditional means in order to protect his colony from the dangers of extremism.

His was a vision that reached the heavens, but that was grounded in the earth—just what was needed for a successful colony in a harsh land.

The Legacy

Winthrop’s “Christian Charity” message—one that encouraged the colonists to “love one another with a pure heart, fervently” so that they could “delight in each other, mourn together, and suffer together”—created an utterly unique sense of community that persists unto today.

That, together with Winthrop’s idea of America as a chosen nation, bound by God to be excellent in all of its doings, made the nation what it is today. Although his influence has now been largely secularized, you can still see his fingerprints wherever you turn, and his enduring metaphor for America continues to guide and shape our nation.

“I think I can see the whole destiny of America contained in the first Puritan who landed on those shores.”

-Alexis de Tocqueville