His friends will reciprocate the greeting by smearing him with their own caches of green and yellow powder. Then they'll head to the York University campus, where the dry-powder streaks will give way to splashes of colored water, and maybe even a rainbow-hued snowball fight.

It's all done in the name of Holi, the Hindu festival of colors, which actually falls on Friday. But Mr. Vyas is celebrating it on Saturday out of respect for some of his friends and fellow students who are Christian. Friday is also, after all, Good Friday, and when you're celebrating Holi in Canada, you sometimes have to make concessions.

The annual spring festival is especially popular with young people, for whom it's an excuse to indulge in an all-out water fight. In India, they get up early in the morning to prepare buckets of colored water and fill water balloons. Later, young people gather and "play Holi" with neighbors, friends, and family, splashing each other and rubbing dry color--called gulaal or aber--on each other's faces.

In Canada, because of the cold weather that typically coincides with Holi, most people have adapted the tradition to incorporate indoor activities. But some die-hard fans, such as Mr. Vyas, will still mark Holi traditionally.

"It's just fun," the 23-year-old York student says with a laugh. "At first people say: 'No, no.' But soon they join in."

The festival is celebrated the day after the first full moon during the Hindu calendar month of Phalgun, which usually falls between late February and late March.

"In India, Phalgun ushers in spring, when seeds sprout, flowers bloom and the country rises from winter's slumber," says Gyan Rajhans, producer/broadcaster of a Vedic religion radio program, "Bhajanawali." "It's like our Thanksgiving for a good harvest."

Mr. Rajhans is originally from Bihar, an Indian province where Holi is celebrated slightly differently. There, people spray each other with dry soil on the day before Holi, he explains in Hindi, and eat sweet pancakes--maal pua--instead of the moon-shaped semolina pastries called gujiya that are the traditional Holi treat in other parts of India.

The tradition of bhang, however, is no different. A mild intoxicant made out of the leaves and seeds of cannabis, bhang is consumed in various forms across India on Holi. "It's usually mixed with thandai, an almonds and milk drink," Mr. Rajhans says. "On Holi, even youngsters have leave to drink bhang. I once drank it, and my father kept on scolding me, but I kept on laughing, because you get the giggles after drinking bhang."

There will be no bhang or water colors at the Bihari Association of Canada's Holi celebration, which Mr. Rajhans helped establish four years ago. But there will be dry colors. Every year, the association rents a hall that allows them to play Holi--as long as they pay extra cleanup fees.

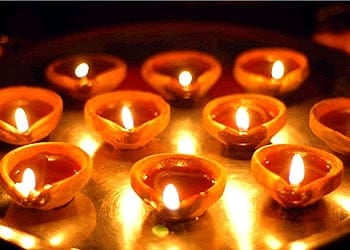

Most of the temples in the Greater Toronto Area mark Holi by burning a bonfire to signify the death of Holika, sister of the demon-king Hiranyakashyap, who, according to Hindu mythology, tried to kill her nephew, a devout follower of Lord Vishnu. Some temples, such as the Vaishno Devi Mandir in Oakville, will have some dry colors for followers who come for weekend prayers.

At the Vishnu Mandir in Richmond Hill, the Sunday gathering will use talcum powder instead of traditional colors. "It becomes messy otherwise," says Manisha Shah, a temple volunteer.

But for Mr. Vyas, who came to Canada in 2000, getting messy is part of the fun of the festival. The first time he played Holi here was on the York University campus. He started with a few friends and ended in a water fight with 25 people.

Since then, they've continued the tradition. "The school is fine with it," Mr. Vyas says. "We don't vandalize property or anything like that. And we don't play inside the corridors, so we don't make a mess inside."

And if it's especially cold, he says they won't be deterred. To lessen the shock of an icy splash, he and his friends fill their bottles with hot water, he says. And to avoid getting too cold, they stay close to shelter.

"The [York] Commons are kind of covered from three sides," he explains. "So we go outside and play, and then come inside."

Next Saturday morning, when Himanshu Vyas leaves home to meet a few of his friends, he'll bring along a packet of bright red powder. When he sees them, he'll dip his fingers in the powder and smear a generous daub on their faces, hands and any other patches of exposed skin within his reach.