When was the New Testament composed? When was its earliest publication? Were the Apostles Paul and Peter in Rome’s Maritime Prison?

Tradition says this cistern near Rome’s Colisseum was a holding cell for Peter and Paul

The Bible is filled with history that is crucial to the message of salvation. But however central the history of Jesus and the Apostles to the gospel, careful reading of the New Testament reveals that the chief message is Jesus himself, his teachings, and his Kingdom. The four gospels and the book of Acts include extensive narratives, but there are large gaps in the life of Jesus and the Apostolic Church that skeptics and revisionists have exploited, while believers are hungry to know what did transpire in those periods. The same is true of the writing of the New Testament. Aside from brief information in the epistles, the prologues of Luke’s gospel and book of Acts, and John’s description of his circumstance in the writing of Revelation, the New Testament has no narrative covering its writing. Skeptics and revisionists have likewise exploited that, but believers also want to know how we got our New Testament.

Jars at Cana which tradition says may have held the water Jesus turned into wine

For the Christian faith to have validity, we need not have the words of Jesus precisely as he spoke them so long as we have an accurate summary of his teaching and of the crucial things that he said and did. John declared that it would have been impossible to record everything that Jesus did. (John 21:25) The Holy Spirit would have brought such things to the Apostles’ memory as was needed for the gospel. But importantly, the New Testament must actually preserve the testimony and teachings of the Apostles, something that “believing” scholars may overlook. That is because Jesus declared that his message would be conveyed to the world through his Apostles whom he chose specifically to witness his days on earth.

It informs our understanding of Jesus to know how the Apostles understood him prior to his resurrection. They reckoned him as Israel’s Messiah, but how did anyone in Israel then understand the Messiah? The New Testament makes it plain that it was not until after the resurrection that the Apostles understood Jesus’ teachings about the Kingdom of God. Their understanding may not be altogether from his post resurrection appearances. Jesus declared that the Holy Spirit would bring the needed understanding to the Apostles, a record of which their scribes or pens wrote down.

What this means is that any supposed development in understanding Jesus that scholars may see in the New Testament had to take place during the ministry of the Apostles as more was revealed to them by the Holy Spirit. Any new teaching of the Holy Spirit would have added more light to what had come before. Else we do not have the witness of Jesus and the incarnation was to that extent a waste! Who cares

what was written by those who were not inspired by Jesus, whether by Gnostic writers or orthodox church men!

At Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, tradition says is the spot where Jesus was born

Responding to ancient skeptics and revisionist teachings about Jesus and to the questions of believers, the Early Church fathers compiled a bit more information about Jesus and the Apostles than appears in the New Testament. Some of it concerned the writing of the gospels. That even the Early Church fathers had the same questions as we do today about what the New Testament did not say, add so little to what it did say, and used much the same extra-biblical sources (apostolic fathers, Josephus, pagan Roman writers) suggest that this history was lost from the earliest days of the church. That needs explaining, but all that was ever vital was the testimony of the Apostles.

This also indicates that the New Testament books had become established from a far earlier day than presently acknowledged. If prominent churchmen of the early centuries questioned certain books, as is still the case for those who do not like what those same books say, there could hardly have been a long process of canonization as current scholarship pretends.

John Locke

Interestingly, the fathers of the Enlightenment such as John Locke and the first liberal (Unitarian) churches in America declared with the Early Church and against orthodox theologians of their day that the Christian faith had been established by the great and public miracles of the Apostles. For them, that was the reasonable way in which the Christian faith had become established. In fact, the traditional histories from the Early Church served believers until the rise of the skeptical histories of the eighteenth century. Those began as rationalist attempts to explain away the New Testament miracles, attributing the New Testament to a creation of the Church rather than having originated with the Apostles. That resulted in a late dating of the New Testament, most of it supposed to have been written well into the second century.

If the most outrageous claims of the skeptics have been refuted by careful historical research, if different motives drive the writing of new revisionist histories, if the dates of the gospels have been lowered to the later years of the first century, and if new techniques have been added to the profession, the methods of literary criticism introduced by the skeptical scholars launched the way that modern biblical scholarship is still being done. To understand, I quote from another author who worked on New Testament history from outside, A.H.N. Green-Armytrage in his John Who Saw (1951):

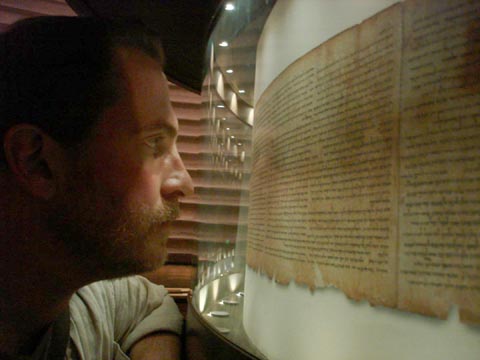

Studying the Dead Sea Scrolls in Jerusalem

There is a world – I do not say a world in which all scholars live but one into which all of them sometimes stray, and which some of them permanently inhabit – which is not the world in which I live. In my world, if The Times and The Telegraph both tell one story in somewhat different terms, nobody concludes that one of them must have copied the other, nor that the variations in the story have some esoteric significance. But in that world in which I am speaking this would be taken for granted. There, no story is ever derived from facts but always from somebody else’s version of the same story….

In my world, almost every book, except some of those produced by government departments, is written by one author. In that world almost every book is produced by a committee, and some of them by a whole series of committees. In my world, if I read that Mr. Churchill, in 1935, said that Europe was headed for war, we applaud his foresight. In that world, no prophecy, ever how vaguely worded is ever made except after the event. In my world, we say ‘The first world war took place 1914-1918.’ In that world, they say the world-war narrative took shape in the third decade of the twentieth century.’ In my world men and women live for a considerable time – seventy, eighty, even a hundred years – and they are equipped with a thing called memory. In that world (it would appear), they come into being, write a book, and forthwith perish, all in a flash, and it is noted of them with astonishment that they ‘preserve traces of’ primitive tradition’ of things that happened well within their adult lifetimes.

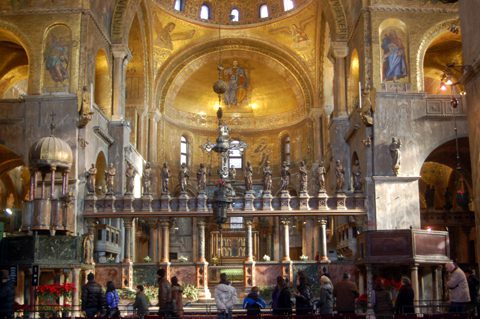

Mark the Apostle’s tomb in Venice, Italy

In short, such literary criticism of the Bible is not about men, events, and the great acts of a living God, but about texts, traditions, and theological agenda. The product – God help us! – is a New Testament in the image of literary scholars, but not what anyone should want to know. Disappointingly, even conservative studies of the New Testament follow the same principles of literary criticism and thus are but modifications of the composition histories of the nineteenth century. Whatever new methods scholars now employ, they preserve the original focus on texts and traditions rather than on men and events, the Holy Spirit turned into mere theology (theory). Worse, “conservative” New Testament histories accept the notion that some of our New Testament books do not date from the Apostles. Any work of scholarship ought to be an honest judgment of the facts, but if our

New Testament is truly not the testimony of Jesus’ Apostles, that is deadly to the life and power of biblical faith.

Mars Hill on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, where Paul preached

Ironically, the first modern challenge to the revisionist histories in favor of an Apostolic era dating of the New Testament came from a scholar more famously known for launching the ‘God is dead’ controversy of the sixties. I had the privilege of hearing the brilliant Bishop John A.T. Robinson, then Dean of Cambridge’s Trinity College, not long after the publication of his Redating the New Testament. Robinson’s thesis was that due to the lack of reference to the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 as an accomplished event, all the books of the New Testament had to date prior to A.D. 70. Though I disagree with many details of his chronology, Robinson’s main thesis is substantially sound. He avoided much discussion of authorship, but Robinson well knew that his early dating was compatible with these writings being substantially the work of the Apostles.

There is another historical event that Robinson might have better used for dating the New Testament. This was the day that Emperor Nero instituted orders that turned Christianity into an illicit religion, resulting in the cruel persecution of the Christians and the martyrdom of Peter and Paul a few years prior to A.D. 70. Aside from a single passage near the ending of the gospel of John and the abrupt ending of the book of Acts, there is no hint in the New Testament of these Apostles’ actual demise. Nor is there explicit mention of the great Neronian persecution, so famous in the ancient world and of great significance for the Church. Some attribute the Apocalypse of John to that event. Though I am not convinced of that, I submit that the Neronian persecution is very present in several of the letters of the Apostles and explains why these same epistles are so cryptic in terms of authorship and narrative and so proper with regard to the Roman authorities.

Hadrian’s Arch and the Colisseum in Rome

I suggest that this sudden outlawing of the Christian faith in the Roman Empire also explains the great gap in reporting Christian history immediately following the New Testament. I strenuously disagree with the claims that this persecution was limited to the Christians of Rome. If the Emperor did not himself extend it, his edict would have soon come to the attention of the enemies of Christians throughout the Empire. It became the first occasion for Jews to separate themselves from the Nazarenes, Jewish Christians. Though for the next several centuries, persecutions were driven by local opposition, the Imperial decision had to remain effective. We see prosecutions focused on Christian allegiance to the Emperor.

Christian writers understood that publishing details about the apostles and the church would have put both those who protected the apostles and the affected churches in grave danger. But, as would be the case of the persecutions in the centuries just before and after the Reformation, outlawing the faith made the need for Scriptures all the more important. Because and in spite of these dangers, I submit that it was immediately following the martyrdom of Peter and Paul that the New Testament books were first collected and published as a definite collection.

A big reason for the lack of scholarly attention to this persecution is due to Roman Catholic exploitation and Protestant bias against the ministry of Peter in Rome. That should be relegated to the past. Everyone should better know the traditions preserved in Rome of the imprisonment of Paul and Peter. We may have no ancient record of the Maritime Prison as the site in Rome where Paul and Peter awaited their execution, but that doesn’t mean that the traditions about this prison can be ignored. Aside from what seems a few medieval accretions, these traditions have more the flavor of the accounts of the Apostles in the New Testament.

The Apostle Peter’s tomb beneath the altar at the Vatican

I have in mind the reports of a revival in the prison as Paul and Peter awaited their execution, memorialized in the bronze casting (pictured above) that visitors today see inside the Maritime Prison. A revival isn’t a very Catholic type of thing to remember, but revivals in prisons are not unknown in the New Testament. Not just the letters of Paul, but even the gospels and the book of Acts give much attention to imprisonment. Those imprisoned on account of their ministry had an altogether different kind of ‘prison ministry’ as we see today. As we learn from this tradition, every prisoner awaiting in this cell along with the prison warden himself was converted while Paul and Peter were awaiting their execution.

It is fitting to the entire context of what we know about these things that the Imperial warden of the prison would have been none other than Theophilus, for whom Luke wrote his gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. The synoptic nature of the gospels and the particular epistles included further suggest that Luke and Theophilus published the first New Testament. Their publication would have included all the books aside from those written by the Apostle John. The book of Jude may have accompanied this distribution as one of the living brothers of the Lord confirming the New Testament as the faith once and for all entrusted to the saints.

One reason for believing this is that the books of the New Testament so envelop the contacts and travels of that one man who gave us our only history of the New Testament Church. Consider that Luke would have possessed not just the gospels he reports to have consulted, but also the letters of the Apostle Paul, his own hand having been involved in the penning of many of them. Obtaining copies of the epistles that Peter wrote from the same city would have been no less inconvenient.

As I will explain, this same team may have delivered another important letter from the Apostles to the Hebrews in Jerusalem.

Slab in the Church of the Holy Sepulcre where tradition says Jesus’ body laid

If I venture to speculate about these matters, I do so as did John A.T. Robinson, in careful consideration of the chronology and character of these times. Those constraints are far better than can be said of the speculation of unheard of texts and undocumented traditions that scholars regard as fair game in their profession. As in the case of Robinson, I am not in the least dogmatic about what I see as excellent possibilities that should be tested against all that we know about these men and their times.

There are several things that distinguish my attempt at obtaining a New Testament history. The most import is a focus on historical men rather than supposed texts. Added to this is my deep conviction that the Apostles and the brothers of Jesus worked in one unified body, just as the New Testament and church fathers attest. From these primary sources, we learn that Peter, John, Matthew, Paul, Barnabus, Silas, Apollos, and Philip the Evangelist worked in the same cities. The Apostles often used the same assistants such as Mark, Timothy, Titus, if not also Luke and numerous others such as Priscilla and Aquila mentioned in their writings. They lived and worked as a one big family. I also believe that all the Apostles traveled frequently if not so greatly as Paul, though Luke had the most acquaintance with Paul and Peter.

Another difference is my assumption that all the Apostles, including Peter were literate. They may not have been trained in the classic style, but the Apostles were not peasants. They were freeborn Jews instructed from early age in the Law of Moses. Religious teachers especially needed to read and write. Of course, one wanted the best hand if not a specially trained scribe to assist in writing letters. Much of New Testament scholarship ignores the evidence of widespread basic literacy among the Jews as they also ignore the impact of Christianity in spreading common literacy. Like the Judaism that preceded it, Christianity requires literacy and produces the literacy that it requires. Christian missionaries have bestowed the tradition of common literacy to the entire world.

Jean-Leon Gerome’s classic painting “The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer”

Because the traditions report that the Apostles were not killed in the earliest Neronian persecutions, likely neither Peter nor Paul were in Rome when the persecutions began. Peter may have fled, as tradition tells us, just as he had fled Herod’s earlier attempt to kill him. Jesus instructed his disciples to flee persecution. (Matt 10:23). But these men were too prominent not to have been main targets of Nero’s injunction. It was too easy for the Emperor to summon them to Rome. Jesus had warned Peter that when he was old, he would be bound and taken where he did not want to go. (John 21:18-19) Neither Jesus nor Peter would have wanted believers to be martyred without joining them in their suffering.

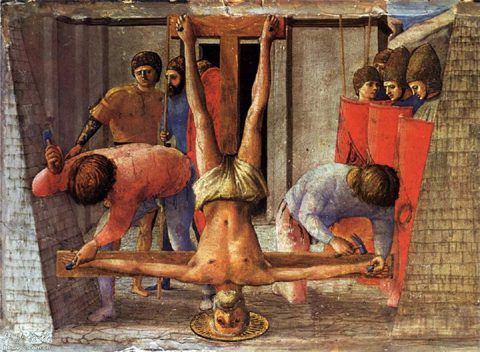

Peter’s crucifixion — upside down — in Rome

The Apostles would have been brought to Rome as dignitaries for execution, with plenty of opportunity to write letters from prison. It is reasonable to suppose that both letters of Peter and perhaps Paul’s second letter to Timothy were written from Rome after the time of their summons. If Peter was was in Asia when summoned to Rome, there is reason to suspect that the believers there may have experienced the same burnings (1Pet 4:12) as occurred at Rome. In this is the case, Peter wrote his first letter back to those he had just left.

In a recent newsletter (click here for article bottom left in Volume 2, Issue 10), I mentioned the possibility of the book of Hebrews being a joint composition of Peter and Paul written during their joint imprisonment in Rome to the Church in Jerusalem following the death of James, the brother of Jesus. It is sometimes claimed that the canonical status of the book of Hebrews was slow to be accepted in Rome and the West. What is actually the case in Rome and the West was reluctance to attribute this book to the Apostle Paul. Those in Rome would have remembered a more complex history for this letter. Paul may have been involved, but the voice is more that of Peter. The

easy authority concerning the Hebrew Christians following the death of James has certainly to be Peter’s alone.

Medieval church door showing tortured Christians

Silence and ambiguity about the author of Hebrews is explained by the circumstance of its writing. Not that it would so much affect the fate of Peter and Paul, but it would surely incriminate Theophilus and Luke. Reference to the Apostles in Heb 2:3,4 as someone other than the writers is justified by the letter being a joint composition and necessary to protect the official who allowed this letter to be composed and delivered after the Imperial edict. Was Theophilus (lover of God) the prisoners’ nickname for their beloved warden. Perhaps, Luke avoids mention of Paul’s latest journeys in the book of Acts not only because Theophilus already knew about Paul’s last activities but also to protect those in the provinces who had given Paul shelter after the issue of Nero’s edict

Their lower profiles may have enabled Theophilus to protect Luke and release Timothy, as noted at the end of the epistle to the Hebrews. If the Apostles words end with the Amen at the end of verse 21, as often mark the end of books, I don’t think “in few words” in verse 22 applies to this long book, but to what was added.

Heb. 13:22-24 And I beseech you, brethren, suffer the word of exhortation: for I have written a letter unto you in few words: I want you to know that our brother Timothy has been released. If he arrives soon, I will come with him to see you. Greet all your leaders and all God’s people. Those from Italy send you their greetings.

In verse 13:19, the chief author of the epistle to the Hebrews is still in captivity, but the author of this note is free to accompany Timothy on a journey. If that is Luke speaking, he may be signaling his intention to bring the first New Testament to the church in Jerusalem. Luke and Timothy may have been planning a mission to carry the first New Testament to all the major churches.

The first publication of the New Testament may have been less simple than the picture I have just given, but the simplest explanation is surely the place to begin. Whatever the actual case, it should be clear that scholars have little considered how the composition of the New Testament so well fits the last days of the Apostles, and how the publication of the New Testament fits the time immediately following their martyrdom. How else to explain the rapid acceptance of these writings throughout the church had they not reached the hands of those who knew the Apostles?

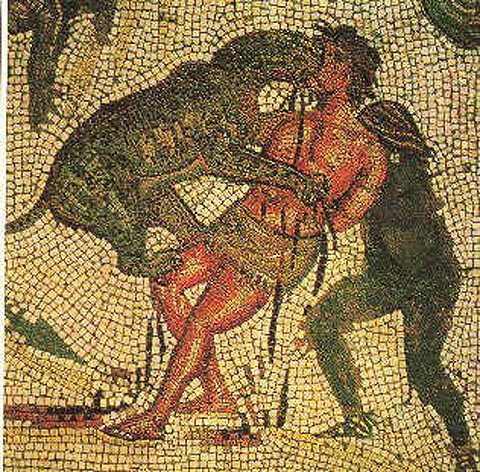

Roman mosaic of a Christian being fed to a lion

This great persecution and turning Christianity into an officially illicit religion explains the great silence in Christian writing in the generation immediately following the death of the Apostles. The silence is all the more remarkable when one considers the evidence that the new faith exploded throughout the world in the days of the Apostles, far more than currently acknowledged. During all ages of the faith, persecution has been directly proportional to Christianity’s expansion, not the other way around as many today improperly teach. During the days of the Apostles, the faith was known by nearly everyone in all parts of the Roman Empire and in many regions beyond. This is not to say that many circles of ancient Jews and pagans were much interested in what sophisticated pagans perceived as a particularly pernicious Jewish superstition, but everywhere folks were aware of its existence if only from the riots and disturbances due to the impact of the faith on ancient religion.

It is fitting that the testimony that became the foundation of our faith came after many years of Apostolic service and in the midst of their greatest persecution. To keep the testimony of those who knew Jesus undiluted and confused by later writings, the Early Church recognized how important that the testimony about Jesus be restricted to those who actually knew him and the writing of their testimony to those who assisted the Apostles. So far as concerns the faith, there was far less need for writings about Jesus following the death of those who knew him and who Jesus had commissioned to make his testimony.