As I had once been in charge of the Agency, I was later asked to describe its people and places. The Agency is redolent of the British imperial encounter with Asia: The diplomatic manuevering known as the Great Game, the Durand Line, tough terrain and tougher tribes -- n this case the Wazirs and Mahsuds, described as "panthers" and "wolves" by Sir Olaf Caroe in his book, "The Pathans."

This is quintessential Rudyard Kipling territory.

One of Kipling's most famous literary creations, Kim, was a child of and played in The Great Game. Although the title may suggest a friendly sporting contest, The Great Game was played in deadly earnest. It was played for power and prestige by the imperial powers--Russia, China, and the British --in the valleys and mountains of Central and South Asia.

As Kim discovers early on, nothing was as it seemed. Even the so-called political officers were not political, but drawn from the elite civil service cadre.

The South Waziristan Agency and the North Waziristan Agency together constitute what in the area is called Waziristan--the land of the Waziris. The South Waziristan Agency is about 4,000 square miles with mountains as high as 11,500 feet. Temperatures go up to 120 degrees in summer and drop below freezing in winter. The terrain is harsh and mountainous and the settlements scattered far and few between.

With these tribes and this terrain, entire regiments of al-Qaida and the Taliban could move about without detection. As for Osama, I told ABCNews, he could swim like a fish in an ocean.

I had held similar key field posts before, but Waziristan was special.

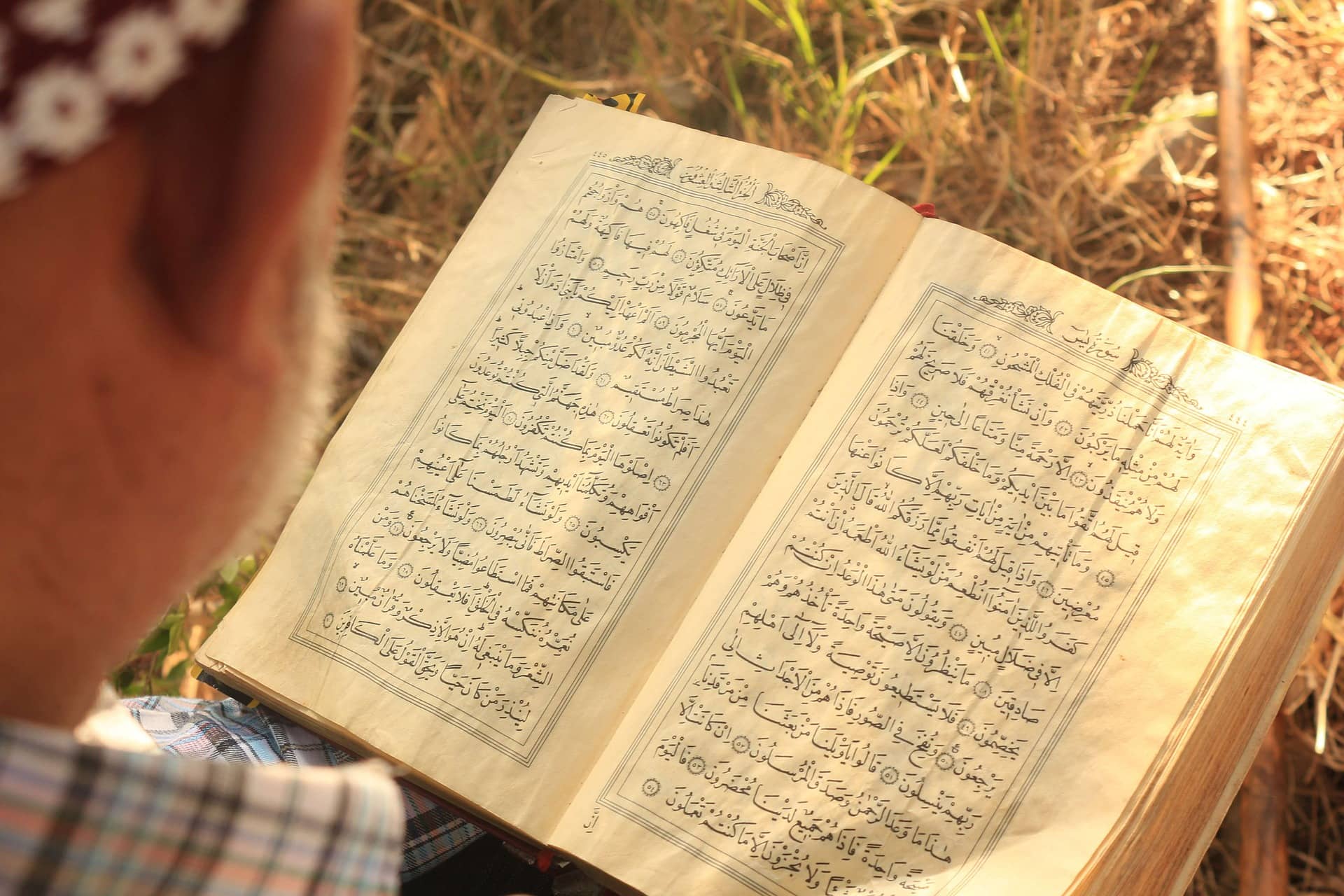

Later, I wrote about my time in the Agency, hoping to provide an ethnographic account and general principles of what was happening in Muslim societies. The account eventually became the book "Resistance and Control in Pakistan." At the time, I was struck by the rise of religious leadership that was prepared to challenge established government authority. I was also fascinated by the case of Mullah Noor Muhammad and his creation of the madrassah, or religious school, in Wana. Looking back now, it seems that the madrassah was the harbinger of things to come in the region. The Taliban who would go on to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan and later occupy Kabul would be products of such madrassahs.

Recently I phoned Azam Khan, the present political agent for an update. The elders, he said, were ineffective and seriously challenged by the young generation. People wanted to connect with the rest of the world and the young in particular were restless for change.

American troops, trying desperately hard to stay on the Afghanistan side of the international border while pursuing Osama, al-Qaida and the Taliban, found themselves having to take a crash course on the Great Game.

Things were never quite what they seemed in this part of the world. The international border was nonexistent on the ground in many places and was disputed in others. Not for the first time in history would soldiers from distant lands with ideas of superiority have to contend with the powerful tugs and pulls of the currents emanating from Waziristan.

Informers and those suspected of helping the American or Pakistan army were swiftly and brutally executed. Religious leaders were already beating the war drums. If American troops enter Waziristan they will stir a hornets' nest, which will make Iraq look like a picnic on the lawns of the White House.

Now with the world media discovering the Agency in the search for Osama bin Laden and dragging in all the appurtenance of our contemporary interconnected world, such as satellites that can pick up and enlarge photos of every little scrub in the most remote ravine, I wondered how the encounters would change Waziristan.

Their tribalism, I think, has been both a blessing and an affliction. It provided stability in unstable times but also created complications in changing times. This theme of continuity and change, of resistance and control, so apparent in Waziristan, lies at the heart of Muslim society and partly explains the turmoil in it.