Sorrow is clarifying, but not immediately. In proximity to death and destruction, it is easier to feel sharply than to think sharply; and for this reason mourners rely on rituals and liturgies, on the conventions of grief. There are times when brilliance is not the most important thing. If platitudes provide comfort, then let there be platitudes, at least while the wound is fresh.

Sorrow is clarifying, but not immediately. In proximity to death and destruction, it is easier to feel sharply than to think sharply; and for this reason mourners rely on rituals and liturgies, on the conventions of grief. There are times when brilliance is not the most important thing. If platitudes provide comfort, then let there be platitudes, at least while the wound is fresh.

So it was without rancor that I noted the platitudinous manner in which Daniel Pearl's superiors at The Wall Street Journal, Peter Kann and Paul Steiger, responded to the shocking news of his murder. They reached for what the emotional folkways of America could give them. Their statement of February 22 strived for dignity. It surpassed its objective: what Kann and Steiger said was excessively dignified, in a way that might be harmful to a proper analysis of the outrage in Karachi.

"His murder is an act of barbarism," they asserted, "that makes a mockery of everything that Danny's kidnappers claimed to believe in."

Regard this sentence closely. The slaughter of this good man was certainly a barbaric action; but the precise sin of which Kann and Steiger have accused Pearl's killers is hypocrisy. The editors of the Journal denounced them as bad Muslims!

It goes without saying that cold-blooded murder is a violation of every religion's teaching, but what is most horrifying about cold-blooded murder is surely not that it is a sin. Indeed, what is true about the death of Daniel Pearl is the very opposite of what Kann and Steiger said about it. Kann and Steiger are correct to suggest that the origins of this deed are to be sought in a system of belief, but they have it backwards. The slaughter of Daniel Pearl did not make a mockery of what his slaughterers believe. It was the perfect expression, the inevitable consequence, of what his slaughterers believe.

If the worldview of Pearl's abductors--who appear to have belonged to a radical Pakistani group called the Army of Muhammad--was an Islamic worldview, it was one of many Islamic worldviews. This much should be obvious. But it is not plain to Kann and Steiger, who have clearly been so intimidated by the possibility of the appearance of intolerance, so inhibited by the prevailing post-September etiquette of never uttering a critical or choleric syllable about anything Islamic, so imbued with the American delegitimation of anger, that they chose to meet the news of their colleague's hideous slaying with a mechanical vindication of the religion of his slayers. As if the proprieties of American pluralism are to be extended also to the Army of Muhammad!

It is worth noting, surely, that there are situations in which anger is a sign only that you have understood events correctly. To be sure, anger must be allowed to pass away; but it must also be allowed to come into being.

The murder of Daniel Pearl was a symbolic act. It was conceived as the expression of any or all of the following beliefs: that America is evil and therefore all Americans are evil; that the individual is never anything other than the representative of his group; that religion (and always one religion) must rule the world; that democracy is a poison and must be prevented by violence; that violence may be numinous, a lofty fulfillment of the soul; that the history of the world is a clash of civilizations in which one civilization will live and all the other civilizations will die; that the West has nothing to offer the world but colonialism; and that all of the inquities of modernity, the entirety of the threat that it poses to traditional societies, in this case to traditional Islamic societies, is chiefly and most completely exemplified by the Jews.

"I am a Jew, my mother is a Jew": these are the words that Pearl is alleged to utter on the videotape of his murder, the words that provoked his killer to cut his throat. I cannot recall in recent memory a more unreconstructed example of what we prefer to think of as "medieval" anti-Semitism. The connection between Pearl's affirmation of his Jewishness and Pearl's death was a causal connection. This could not be more plain.

And there is no irony for the killers and their supporters in the fact that the Jew whom they beheaded was a secular Jew, because that merely compounded Pearl's transgressions, and because they are not creatures of irony. Indeed, it is their inability to comprehend the adjectival benefits of "secular" that defines their historical imprisonment. What they do not admire they murder. Their instrument of criticism is the knife.

Owing to the manner in which he died, there will be Jews who will regard Daniel Pearl as a martyr. I have already heard Jewish friends say as much. And the circumstances of Pearl's death are eerily consistent with the requirements of martyrological status in Jewish law and Jewish tradition.

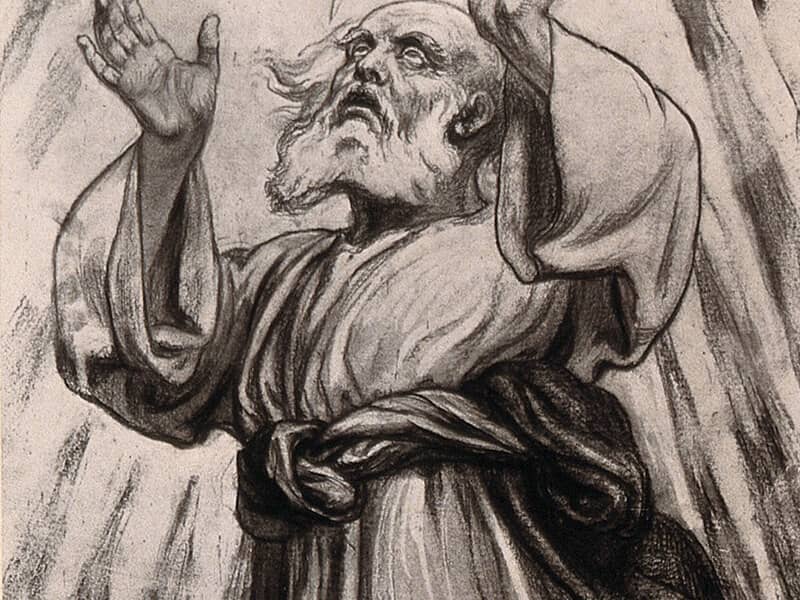

This savage execution puts one vividly in mind of the rabbinical rhetoric of "the Sanctification of the Name." (Here is a random example, from a sermon by a sixteenth-century rabbi in Salonika, commenting on the Psalmist's verse "for thy sake we are killed all the day long": "The Psalmist wishes to say that we regard ourselves daily as if the knife is placed upon our throat to slaughter us for the sanctification of the Name.")

But such an interpretation must be ferociously resisted. To regard Daniel Pearl as a martyr--a martyr for Judaism, a martyr for America, a martyr for modernity, a martyr for democracy--is to concede too much to the perpetrators of his death. Holy victimizers will not be defeated by holy victims. Instead the notion of sacred historical necessity must be repudiated.

This will not be easy in some parts of the world, where politics is still eschatological (and therefore not, strictly speaking, politics at all). History is once again choking on God. But the murder of Daniel Pearl was not a martyrdom, it was an atrocity. Is that not stirring enough? And the beauty of his life is reason enough to lift his memory high. Martyrdom is not the only way of dying not in vain.