Sara first visited my family during the Jewish holiday of Passover. We had been dating only six months, and as an observant Jew, Sara had strict dietary restrictions unfamiliar to my family and me. My mom and I agonized over whether rice constituted leavened bread and how we would find enough drinks and desserts made without corn syrup to last a few days. Sara ended up with food on her plate, but the visit gave me just a glimpse of the learning I would undertake as our relationship grew.

Now, three years later, Sara and I are engaged. I'm living in a kosher house, and learning Hebrew and Jewish customs. I'm three months away from a Jewish wedding and two weeks away from converting to Judaism.

Long before I met Sara, I joked about wanting to marry a Jewish girl. It was an easy way, I laughed, to help ensure my kids would become cardiologists and pianists and that I would summer on the Jersey Shore. The stereotypes weren't mean-spirited; I was simply fascinated with Jewish intellectual life, and I hadn't thought seriously about Judaism, its culture, history, and language. Now, my joke is no longer a laughing matter. I've known Sara and her family for four years, but the transition to joining a Jewish family has been a challenge.

My own parents met at Wheaton College, a small Christian liberal arts school west of Chicago. Wheaton's curfews, house mothers, and bible study sessions matched the values my parents' families had learned from listening to Billy Graham's Sunday radio show. My parents fell in love, married, and after two years in the Mennonite Service Corps in Bolivia, moved to the Chicago suburbs.

As a kid, I attended the First Presbyterian Church in Evanston, Ill. My brother, sister, and I sat dutifully through the first part of each week's service, waiting to sip communion grape juice, stuff a dollar into the collection basket, and run off to Sunday school. After classes, we enjoyed cookies and hot chocolate, and then rushed our parents home to turn on WWF wrestling, substituting body slams for bible stories. The three of us spent summers at Honey Rock Camp, a Christian camp in Wisconsin, where amidst the chaos of canoeing, fishing, and playing capture the flag, we studied the bible and prayed before meals and bedtime. Church and camp reinforced what I saw at home--faith, support, and acceptance.

In college, I majored in Religious Studies with a focus in Eastern Religions. I began meditating and studying Buddhism, and I spent a semester in Thailand, where I lived at a Buddhist monastery, learning Thai and waking up at four in the morning to chant and then beg for food with the monks. I followed this semester with a summer at a Trappist monastery in Belgium, where the monks' vow of silence contrasted with the gregarious Thai community. In both settings, I found myself surrounded by foreign custom, religion, and history. Ritual that had endured hundreds of years could still be sensed in the smell of incense, in the chanting reverberating in the chapel as evening descended, and in stones worn smooth by the shuffling feet of silent monks. By my senior year, however, my experiences had led more to an interest in the sociology of religion than to discovering my own beliefs.

Soon after college, I met Sara, when we were both Teach for America teachers in Washington, DC. We met through my roommate, who taught fourth grade along with Sara. I shared my old joke with Sara--regarding my reasons for marrying a Jewish girl--and she laughed that while her father and all three uncles were indeed doctors, her family had yet to produce a pianist and owned no property on the shore.

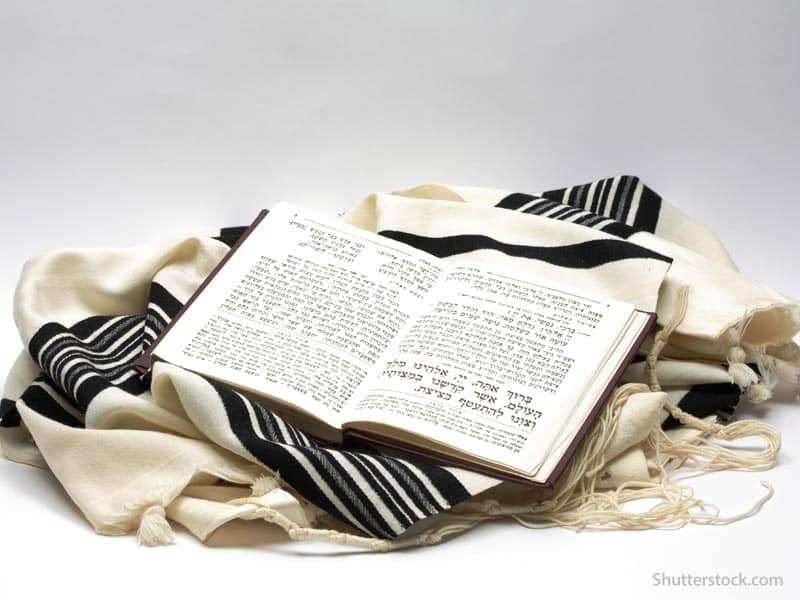

I learned quickly that when you marry a Jewish girl, you marry her entire family. Sara and her family are Conservative Jews, with a strong sense of tradition and identity. Sara's immediate and extended family keeps kosher [Jewish dietary laws] and they are nearly shomer Shabbos (they don't work or write on Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath, though turning on lights and dialing the telephone are acceptable activities for them). They celebrate all the holidays with extended family, large dinners, and synagogue attendance.

I first entered this new world as a visitor. The practice, the songs and blessings, the history, and feel of Judaism were foreign to me. I watched with respect and participated when able--learning the motzi (the blessing over bread) if only for challah French toast in the morning--but always as an outsider. Sara's family welcomed me and taught me about their culture, history, and language. As I fell deeper in love with Sara and prepared to propose, I grappled with the reality that this world would soon become my world and that in place of respect I would need to substitute understanding, identification, and belief. I would need to leap faiths.

That leap began six months ago. Now living in Boston, I contacted the Gerim Institute. "Gerim" means "convert" (or "stranger," which might have made more sense in my case), and the Institute provides two annual six-month introduction to Judaism courses for prospective converts. My class began in January and comprised 20 people. Most of us would-be converts were there because of a future spouse and had enrolled in anticipation of an imminent marriage. Classes end conveniently early in June so that we're packaged and ready to go by the summer's nuptial rush.

I'm not sure what motivated my non-Jewish classmates--genuine desire or insistent prompting of a loved one--but for the most part those who were there with a future spouse would not otherwise have been. I had misgivings. I was apprehensive and when asked at the first class what had attracted me to Judaism, I found it difficult to articulate my desire beyond "I want to marry Sara and she wants to raise a Jewish family." This was my decision, but not my choice; and this tension would surface throughout the conversion process.

During the past three and a half years, I had grown to respect and involve myself in Sara's world, but I was more attracted to Sara than to Judaism. I was skeptical of the conversion process. Would my early Christian experience, which had stabilized and given meaning to my life, be supplanted with this new "identity?" How would I share my Christian background with my children? What about those Christmas Eve nights where we listen to hymns and hang Grandma's antique ornaments on our Christmas tree? Would I ever feel Jewish? Sara and I, our families and friends, and my Gerim classmates, struggled to answer these questions for the next six months.

Coming next: Would I ever really feel Jewish?