In common usage we now think of a Cassandra as a "doomsayer." When someone is too pessimistic we call him or her a `Cassandra.' But Cassandra was not a pessimist; she was a prophet. She cried "doom" to be sure, but we forget, in our stubborn hopefulness, that Cassandra always proved right.

We suffer from a sort of historical Cassandraism. We do not disbelieve prophecies of doom. Indeed, in an age of terrorism they surround us. Rather, we do not take into account the terrors of the past. Sometimes there is literal disbelief, such as the comments of the unspeakable "Holocaust deniers." More often it is not actual rejection but a cavalier forgetfulness. To ignore the past can be almost as pernicious in its effects as to actively deny it.

While we are told the truth about what happened in the past century, we dismiss it or forget it. World War II, the single greatest cataclysm in human history, is turned in popular culture into a stirring paean to the "greatest Generation." The First World War, still referred to in Britain as "the Great War" which changed the fate of Europe, of Russia and claimed millions of lives and introduced the horrors of chemical and trench warfare, is all but forgotten by most Americans. We are prodigies of historical amnesia. Cassandra calls out from our past; we turn away.

Sixty years have passed since the end of the World War II and the liberation of the concentration camps. The survivors who remember the horrors are growing old. We hear their voices: This really did happen. Do not forget.

Their insistent tone battles a powerful human need to push away the wounds of the past. One who has suffered a loss is invariably told by others not to dwell on it, to move on, to remember that life is for the living. There is wisdom in this but it is incomplete. For as psychology has taught us, it is the memories we ignore that master us. One cannot grow wise on a diet of the present alone. As Cicero wrote, to forget the past is to remain forever a child.

As the survivors of the camps grow older, their voices are lost. The vividness and immediacy of the pain recedes; books, movies and museums supplant the living voice. And memory, which is ever eager to push away the pain, threatens to elide this mind-numbing event, to turn it into a black hole of history.

Abba Eban, the late Israeli statesman, once remarked that there were things in Jewish history too terrible to be believed, but none too terrible to have happened. There is a consequent danger of seeing Jewish history as an endless succession of disasters and pains, what historian Salo Baron famously called the lachrymose (tearful) interpretation of history.

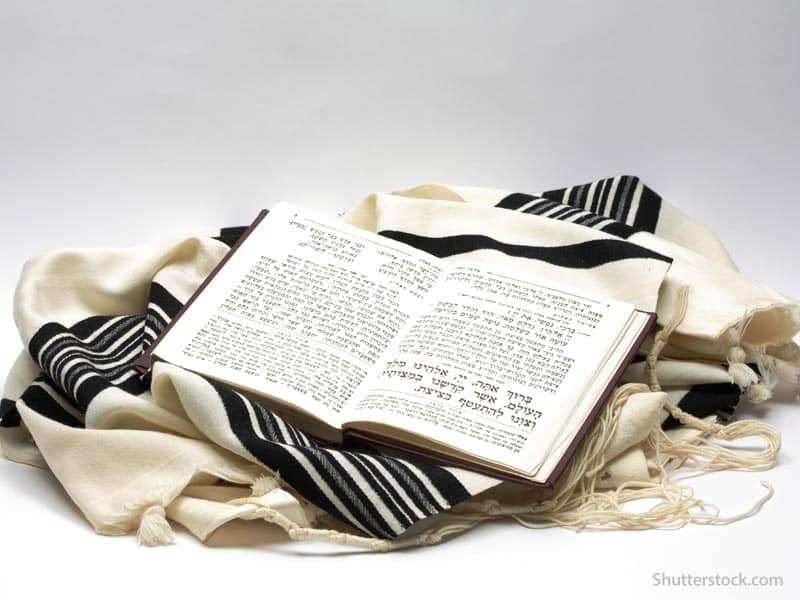

But American Jews are part of a culture in which it is forgetfulness, not memory, that is the danger. What pallid holidays are Veterans Day, Memorial Day, in our culture. In most communities, those who have fallen in defense of America are remembered with a picnic or a department store sale. Yom HaShoah, the day in which we remember those who died in the Holocaust, should press hard on the unimaginable suffering, the innocence, the waste, the destruction.

We remember: that is the duty we owe to innocent suffering. Even if history taught us nothing practical, is not the human community horizontal as well as vertical? Society stretches not only to your neighbor, but also to your grandmother. Her voice is a part of what makes us human. Her memory is part of what makes us whole.

Can those voices, the ones preserved from the abyss, teach us something? William Denson, an Alabama human-rights lawyer who prosecuted Nazi war criminals at Dachau, gave survivors a voice. His practice proved a model of prosecuting others convicted of war crimes. Crucial to the model is to face the sheer horror of what human beings did to one another. Those who are fortunate to live in comfort need the wisdom of those who have seen the underworld. The light is not real without shadow; and our own lives need the weighted voices of pain to give us a true picture of the way the world can be.

As the living witnesses to such barbarity die, the human capacity to perpetrate them lives, so we must not forget.

The holiday of Passover is preoccupied with memory. Why does it dwell on slavery? Surely not because it wants to induce despair or lethargy in those who celebrate, but only the past honestly confronted, only the voices of victims clearly heard, only memory which is not softened by the hazy gauze of good feeling, can ring down through the ages.

We will not forget is not a slogan. It is a prescription for the essential psychic health of humanity. On this [62nd] anniversary of the end of the Holocaust, may we never surrender to forgetfulness, and may the voices of those who died never fade away.

In Greek myth, Cassandra's curse was to be a prophet whose word was doubted. The god Apollo gave her the gift of future knowledge. She foretold what would happen, but no one believed her. Cassandra warned the Trojans not to bring the famous wooden horse into the city. They laughed; then they died.