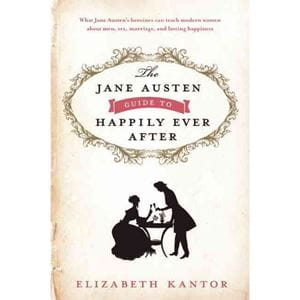

Gayle Trotter: This is Gayle Trotter, and today I’m speaking with Elizabeth Kantor, author of The Jane Austen Guide to Happily Ever After. Thank you so much for speaking with me today, Elizabeth.

Elizabeth Kantor: Gayle, thank you so much for having me.

GT: What can Jane Austen teach us about love? Did she marry and live happily ever after?

EK: She didn’t marry. I think you can make a case for happily ever after in her case, but she did, we have to admit, miss out on the thrilling high point of life that she gets just perfectly right there at the end of Pride and Prejudice with Elizabeth and Darcy. I think in terms of her understanding of happily ever after you have to say that the proof of the pudding is in the eating. If you’re a woman who’s ever been deeply, intensely in love and you read those novels, you see she knew exactly what she was talking about.

GT: How do Jane Austen’s heroines differ on their general outlook on men compared with today’s women and our culture’s common portrayal of men.

EK: Jane Austen was very careful — and her heroines were like this too — were very careful not to be cynics about guys. Jane Austen was well aware of men’s limitations and their foibles. She’s funny about it in her novels, but if her heroines start to get that, like paint them all with a broad brush, all men are jerks — as Elizabeth Bennet says at some point, “What are men to rocks and mountains?” — that kind of man-bashing attitude, then in Elizabeth Bennet’s case, a wise aunt will say, You know, you’re sounding a little bit bitter there. Jane Austen really understands that it’s part of female dignity to respect male dignity. If you want guys to respect you, you have to stay away from that attitude that all men are just jerks.

GT: And why is male attention the ultimate intoxicant and how do Jane Austen’s women react to male attention?

EK: Yes, Jane Austen is just so smart about relationship dynamics and everything. You know how we have this vague cultural memory that back in Victorian times women had to dress modestly so as not to entice men with their physical allurements. In Jane Austen’s day, men were not supposed to pay women attention in a careless, immodest way. They weren’t supposed to be seductive with their attention and their approach to women. Because just like a guy gets his head turned if he sees a girl in a bikini, then often women get our heads turned if a guy pays a lot of attention to us. There’s a chapter in the Jane Austen Guide called “The Real Original Rules: Not for Manipulating Men, but for Helping Women Keep their Freedom” in respect to men. A lot of women, I think, can learn from Jane Austen, essentially relationship rules; rules for keeping enough distance between you and the guy that you can get to know him without losing your perspective on him.

GT: What were Jane Austen’s standards for good temper, and how did she define temper?

EK: I get into temper and also principles and also feelings and all these sort of basic categories for what makes a decent person, as kind of an alternative to… that’s how the women in Jane Austen judge men. Does he have a bad temper? Is he the kind of person who’s always pouting or swearing or generally making life unpleasant for people, or is he the kind of person who has enough self-control that life can be pleasant? That’s just one category of the many categories that she thinks is reasonable to judge people by.

Instead of the modern way where we too often are just going through life and not really thinking about the guys we meet in that objective way. Instead we’re just kind of waiting to be struck by lightning when we meet the one guy who floats our boat, and we don’t think about really what kind of person he is. Jane Austen actually shows you how that works. She has, for example, in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet meets Wickham, and they hit it off right away — he’s obviously her type, they have everything in common, they’re both really fun, social people — and then pretty far into her relationship with him, she suddenly notices, “Wait a minute; do I know anything about him that makes me think he’s a decent person? I’m hearing about him now and what a jerk he’s been in the past; could this be true?”

We think of Darcy as her soul mate, but really Darcy’s a very different kind of person from her and what first makes that love story with Darcy get started is she realizes that he’s an amazing person — that he’s willing to sacrifice himself for other people.

GT: You write in your book about how women need to be polite detectives and that plays into how Elizabeth didn’t know that much about Wickham, but she finds out a lot about Darcy. How does social media in our time make it more like Jane Austen’s world than maybe it was twenty, thirty years ago?

EK: That is such a fascinating question. I got really interested in this while writing the book. Life has been becoming less formal for literally hundreds of years, and it used to be in Jane Austen’s day that you didn’t socialize with people you weren’t introduced to. And if you were introduced to someone, then that meant that somebody was vouching for what kind of person he was.

In the couple hundred years since that time, we’ve obviously moved away from that, and it became totally average and normal for people to socialize with complete strangers and even to do a lot more than just socialize with complete strangers — get really intimate with people they had just met. But it was hard to find out what those strangers were really like. You could tell your story however you wanted to tell it and it was hard for the opposite party to know what you were really like. With the internet and Facebook and all the social media that we’ve got these days, it’s getting harder to hide. It’s getting harder to be somebody who is a complete stranger to everybody, and nobody can find out about you.

In Jane Austen’s day, they talked about what your character was. Having a certain character, which was the kind of person you were and were judged to be by other people based on your past behavior and past conduct.

Now that we’re all leaving a cyber trail, we’re getting, I think, to have a character again. To have a kind of record that we’re leaving that people can find out about. For The Jane Austen Guide to Happily Ever After I interviewed a woman who’s kind of known among her friends as being somebody who’s really expert in finding out about guys online.

She told me a couple of interesting stories about dating a guy and in one case being able to figure out that really she was sort of like a girl-on-the-side for him. He had a girlfriend but wasn’t being honest about it. But she found it out from the web.

GT: That’s very painful.

EK: Yes, it is painful, but the sooner you find out, the better.

GT: Yes, yes. What did Jane Austen see as the most reliable source of happiness in this life?

EK: Jane Austen’s understanding of happiness is — there’s a whole chapter in The Jane Austen Guide where I talk about what she really means by what Elizabeth Bennet calls rational happiness, or permanent happiness. But essentially it’s a kind of balance. Captain Wentworth talks about Anne Elliot as “The loveliest medium.”

That happy medium idea. But it’s not like a boring, not-too-hot, not-too-cold kind of thing. It’s really a dynamic balance where the heroines are walking a tightrope, and it’s exciting every minute that they accomplish being that loveliest medium. Especially in Elizabeth and Darcy’s relationship, what you see is, both Elizabeth and Darcy sort of start out being not in very good balance. She starts out with an instant prejudice against him, and he starts out with a lot of pride and unwillingness to kind of bend to society and be pleasant to folks. And to question himself, really at all.

And in the course of the book, they move, both of them, toward the center and toward each other and learn how to correct themselves and become better people together, and that’s really what their love affair is about. That’s the theme of their love affair — the two of them getting to be better people.

GT: How did the living arrangements of Jane Austen’s day help her characters to be more considerate of others’ needs, and how does our financial independence harm this development today?

EK: That whole financial independence issue is just so interesting in Jane Austen. People think about Jane Austen’s books as being all about some class of superior rich people who are very different from us today.But really, Jane Austen could not afford to have her own bedroom. She shared with her sister all her life. Which is hard, but the fact is, if you have to live with your family if you can’t afford to get your own apartment right out of college, then you pick up some relationship skills that I think are a little bit harder for us today. Today we talk about “working on our relationships” and getting along with a guy, a boyfriend, a husband, seems to us to be really a hard thing. Whereas to Jane Austen, that relationship seemed easier than a lot of others — than the relationship with your parents you’re still living with. And I think she would have been delighted that more people can afford — especially women — to be financially independent. She thought financial independence was fantastic, but she also noticed that it spoiled people. In her books, it’s more the heroes, the guys back then, who are more likely to be financially independent. But she talked about how Willoughby, say, in Sense and Sensibility, was spoiled by early independence, so I think modern folks need to really look out for — maybe some of the problems in our relationships are — we’ve gotten a little spoiled and we’re not used to ever yielding and accommodating to other people.

GT: Why does Jane Austen condemn marrying without love?

EK: She thinks it’s wrong. She thinks it’s morally wrong to marry without love. She calls it “duping somebody,” because he wouldn’t want to marry you if he didn’t think you had feelings for him, right, because that’s just not honest.

But then she also talks about what the likely sad results are going to be. This is in these fantastic letters that Jane Austen actually wrote. She had a correspondence with her niece when her niece was going through the courtship phase of life.So you can not only get the novels and I draw not only on the novels in the Jane Austen Guide to Happily Ever After, but also on these actual letters on advice about whether to marry a guy that Jane Austen wrote. And what she tells her niece is, on the one hand, the guy her niece may want to marry is just perfect in a lot of ways: He’s friends with her family, he’d be a good match, but the niece just can’t get enthusiastic about him or seemed to sort of like him, but now that he likes her she doesn’t like him as much. Jane Austen is saying you just better not get engaged to him without being in love with him because you don’t want the terrible thing that’s likely to happen, which is you’re bound to one guy and then sooner or later someone’s going to come along that you really can like and really can fall for and how awful to be bound to one person and in love with another person.

GT: Right. How did Jane Austen’s heroes differ from Charlotte and Emily Bronte’s heroes?

EK: There’s this great quotation that I love from Florence King who used to write for National Review. She said, “More women have been ruined by Wuthering Heights than by strong drink.” Meaning that the sort of romantic ideal that you see in Wuthering Heights, where Heathcliff and Catherine — it’s a totally impractical match and love story and a bad one because Catherine despises Heathcliff at the same time that she feels like she’s drawn to him and eternally belongs with him and they’re really the same person. So it’s a story of hopeless misery and drama and adventure that makes the protagonists the most interesting people in the world and more authentic than the rest of us who live our conventional, ordinary lives where we may have some passion but we’ve got prudence, too. Well no, no, no; throw prudence aside.

The Bronte ideal is drama and that’s really not what Jane Austen is about. Unfortunately, it’s kind of still a cultural ideal today, that romantic ideal that — as Nicholas Cage says in Moonstruck — “It’s not love unless it hurts.”

GT: Why do you write that Jane Austen was from a time before happiness had become boring?

EK: It has a lot to do with that whole Romantic idea. Up until her day, or a little bit before her day, marriage was going in, I think, a good direction. For hundreds of years, Western civilization has been moving away from arranged marriage toward marriage for love so that in Jane Austen’s books, the ideal is a women gets to choose for herself — she doesn’t have to marry somebody that her guardians and her parents pick. But she’s using prudence. She’s taking into account the kind of things that parents used to take into account. Things like: Will we have enough to live on, does he get along with my friends and family, what’s his character like, is he an alcoholic or a person who has such a bad temper that he’s going to ruin my life. Those very prudent concerns were things that girls were actually supposed to take into account at the same time that they were falling in love. In other words, they were supposed to attempt not to fall in love with a guy who would wreck their life. And then this Romantic ideal with the Brontes and Byron with, as Jane Austen says, “impassioned descriptions of hopeless misery,” come along and persuaded a lot of people that it’s really more interesting to fall into a love that breaks you out of convention and liberates you from normal life and maybe makes you miserable, but isn’t that so exciting? And you can still see that in songs we have on the radio today. And just over the weekend at a party I ran into someone who was interested — she read The Jane Austen Guide and she wanted to talk to me about it — she read the Brontes, she read Wuthering Heights at the wrong time of her life, and it had this big impact on her and made her make a lot of choices that she regrets now.

GT: Is church the best place to find a good man today?

EK: Church is a great place to find a guy and has been for a long time. In the last chapter of The Jane Austen Guide I look at, okay, if you want to be a Jane Austen heroine in the modern world, how could you organize your social life because we don’t have those wonderful Regency balls like where Elizabeth met Darcy? And I think on one end that classic thing that you’re going to meet good guys at church youth group or whatever —the Christian singles group — than you’re going to meet at the karaoke bar. But at the other end of things I think people could also look at things like Match.com and internet dating, and you can put some prudent, rational effort into the project. The problem with a lot of venues for meeting guys today is it’s very difficult to express any interest in a guy without becoming kind of instantly intimate with him. If you meet guys at the kind of parties where the way the guy knows you’re interested in him is that you kiss him at the party, then you’re skipping over all that space that Jane Austen’s heroines had to get to know a guy without getting so close that they lose their perspective.

GT: You share some of your personal dating and relationship history in the book. Which Jane Austen heroine are you most like and why?

EK: Oh, wow. I have never really thought about that one before. I guess personality-wise, everybody thinks they’re Lizzie Bennet, right? In the kind of verbal-social way, I feel like I’ve got more her style. On the other hand, when I was a teenager I was intense, like Marianne Dashwood. Just out there looking for intense — I was definitely caught up in not quite the same Romantic fantasies that she has of her life, but caught up in that, “Pay no attention to convention. Go for intense experiences.” I think we can all see different pieces of ourselves in the different Jane Austen heroines, and we can learn from all the books.