When global leaders convened recently at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, a big question on the agenda was which emerging nation will be the new China.

Will it be India – whose economy has exploded? Maybe one of the Pacific Rim nations, such as South Korea, Singapore or Taiwan?

What about Poland? Don’t scoff! The much-maligned, often-invaded nation which has repeatedly been wiped off the map, is back and stubbornly booming. One reason cited is Poland’s resilience and its deep Christian faith. These are people who refuse to be destroyed. The Nazis and Soviets certainly tried.

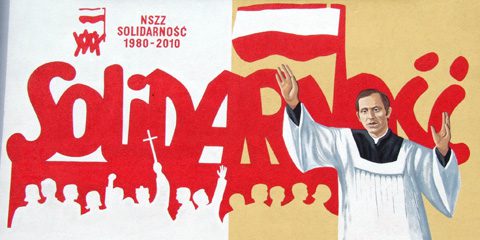

Solidarity faced off againstf the Soviets armed only with their faith (Wikimedia)

Solidarity faced off againstf the Soviets armed only with their faith (Wikimedia)

Back during the Cold War, neighboring Hungary failed to throw out its Russian invaders in 1956. Then Czechoslovakia failed again in 1968. But it was deeply religious Poland that succeeded. A devoutly Christian Polish electrician named Lech Walesa led a grassroots revolt of workers, Solidarity, that captured the imagination of the world.

Standing stern but unyielding beside him was a humble village priest named Karol Wojtyła – better known as Pope John Paul II.

In 1980, when Soviet tanks were ready to roll to crush the Solidarity rebellion, legend has it that John Paul sent a message to the Kremlin. If Russia invaded Poland, the Pope would jet to Warsaw and march out to meet them armed only with his papal staff – with the world’s Christians looking on.

Decades before, Russian dictator Joseph Stalin had scoffed at the power of faith, asking “How many divisions of troops does the Vatican have?”

But this time, Moscow blinked. The tanks did not roll. Poland threw off its Soviet chains.

Within weeks, so did an emboldened Hungary, then Czechoslovakia. When no troops responded, captive Bulgaria, Romania and finally Albania also defied the Russians – and Moscow was powerless to do anything about it.

Within months, the rebellion had spread to Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia and the many captive nations within the Soviet Union itself boldly pulled out – ending 40 years of tension that history calls the Cold War. What Ronald Reagan had declared “The Evil Empire” imploded on itself.

From the Soviet ruins emerged an independent Ukraine, Belorus, Kazakstan – and all the other new nations of eastern Europe.

So, who won the Cold War? American President Ronald Reagan? British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher? Certainly they had a vital role. But it was stubborn Poland that dared to stand tall and lead the way – and they did it looking toward Heaven for guidance and assistance.

Today the world has realigned politically. America has reigned as the economic giant.

It and seven other nations with the world’s largest national economies – France, West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada and a newly capitalist Russia – form the Group of Eight or G8. Together their economies make up 50 percent of the globe’s Gross Domestic Product.

Hovering at the edges are Brazil, India and China. With Russia, these emerging nations are often called BRIC or sometimes BRICS when South Africa or South Korea are included. However, Foreign Affairs magazine has surprising advice from Mitchell A. Orenstein, political science chairman at Northeastern University.

He says the world had better keep an eye on Poland:

“The Polish economy,” he writes, “has grown rapidly for two decades –at more than 4 percent per year, the fastest speed in Europe – and garnered massive investment in its companies and infrastructure.

“Poland’s is now the sixth-largest economy in the European Union. Living standards more than doubled between 1989 and 2012, reaching 62 percent of the level of the prosperous countries at the core of Europe.

“All of this led the World Bank economist Marcin Piatkowski to conclude in a recent report that Poland ‘has just had probably the best twenty years in more than 1,000 years of its history.’”

In the center of Poland’s triumph is the nation’s deep faith.

“An independent kingdom for the previous 800 years, in 1795, Poland was wiped off the map of Europe and absorbed into three great neighboring powers — the Prussian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires — a state of affairs that lasted until 1918,” writes Orenstein. “Reborn following World War I, Poland spent a few short years as a democracy before again being conquered and divided, this time by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, in 1939.”

Nazi execution of Polish priests, 1939 (Wikimedia)

Nazi execution of Polish priests, 1939 (Wikimedia)

“Over the next six years, Poland found itself at the center of what the historian Timothy Snyder has called the ‘bloodlands’ of Europe,” notes

Orenstein. “An estimated five million Poles died between 1939 and 1945, more than half of them Polish Jews. The Nazis and the Soviets also wiped out the cream of the crop of Poland’s intelligentsia and clergy. Warsaw was reduced to rubble, and mass graves were sown across the landscape. Then came four gray and sooty decades of communist domination.

“Only the church offered Poles any hope.”

"During the 1980s, masses were so well-attended that people often had to stand outside the church doors and listen to the priest over loudspeakers," writes historian Brian Porter at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. "If you went to an anti-Communist demonstration in those days, you would be certain to see people holding crosses or icons of the Virgin Mary. There is no doubt that the Roman Catholic Church played an enormous social, political, and cultural role in the Polish People’s Republic, and the fall of Communism would certainly have played out differently were it not for the Church’s involvement. When Cardinal Karol Wojtyła of Kraków became Pope John Paul II in 1978, it was immediately obvious that life would never be the same for the Communist authorities in Poland. Indeed, some have credited him with playing the key role in toppling Communism.

"But exactly how should we characterize the church’s involvement in the great drama of the 1980s? What was the relationship between the clergy and the opposition, and between the clergy and the regime? To what degree did the Pope influence events in 1980 or in 1989? And how did Catholicism shape the views and attitudes of those who opposed the Communist state?

During the early years of the Communist regime after World War II ended and the Cold War began, "the Church was subjected to brutal oppression from the Stalinist state, but in 1956 reformers in the Communist party put an end to the worst abuses and established an informal truce with the Episcopate: the open assault on Christianity would end if the clergy would stay out of politics and recognize the legitimacy of Communist rule.

"Henceforth, the Church in Poland enjoyed freedoms that were unprecedented in the Soviet Bloc. Several independent Catholic periodicals were published (albeit with limited print-runs), the Church could supervise the selection and training of priests, and religious education was even returned to the schools (with restrictions that became more severe over time).

"The clergy remained vehemently anti-Communist and the bishops frequently criticized government policies," writes Porter, "while for their part the Communists conducted covert surveillance on the clergy, set up bureaucratic obstacles to slow the construction of new churches, and used the media to undermine the bishops at every opportunity.

"The growth of an organized democratic opposition in the 1970s placed the Church in an awkward position. On the one hand, the hierarchy was committed to sustaining social peace and feared the consequences of a violent uprising; on the other hand, they were suspicious of the intelligentsia dissidents. Many of the writers, scholars, artists, and political activists in the dissident movement had once been enthusiastic about the promises of socialism, and even as they moved into the opposition they retained the values and ideals of the left. Most of the clergy, on the other hand, still embraced a conservative and nationalistic worldview."

Upon liberation by the allies, Polish Christians imprisoned for their faith by the Nazis(Wikimedia)

Upon liberation by the allies, Polish Christians imprisoned for their faith by the Nazis(Wikimedia)

"With time, however, both sides began to move closer together, recognizing that they faced a common foe. During the late 1970s, it became more and more common for dissidents (even non-Catholics) to hold meetings in Church basements, where the state authorities usually feared to tread. Many parishes became sanctuaries for a wide variety of anti-Communist activists, and important members of the hierarchy (most famously, Cardinal Karol Wojtyła) began to embrace the rhetoric of “democracy” and “human rights.”

"When Cardinal Wojtyła became Pope John Paul II in 1978, this tenuous relationship was further strengthened. In 1979, the new Pope staged a spectacular eight-day pilgrimage to his homeland, and approximately 13 million people -- one third of the entire Polish population -- attended at least one of his public events.

"It's not difficult to understand why the Polish Government was worried about inviting the Pope of Rome to come back to his native land," reported James Reston. who covered the Pope's trip in the New York Times. "He may be more dangerous to the Communist philosophy than all the missiles of the West. For centuries, the Roman

Catholic Church has been Poland's refuge from alien aggressions, and this particular Pope is a symbol of Poland's national identity and faith.

"Nowhere else in this secular world today would it be possible to imagine the scenes this solitary man created in the streets and cathedrals of Poland," wrote Reston. "The people surround his various pulpits like the sands of the sea -- hundreds of thousands of them -- and listen to his message of hope with what can only be described as a kind of silent adoration.

"It was not only that he repeated the ritual and 'comfortable words' of his church. It was the way he talked about the sufferings of the past, and the future of our children, and how he looked on the children and touched them with the utmost tenderness and attention.

"When the Pope arrived in Warsaw and kissed the ground, he said: 'I come to my homeland. It has a particular meaning for me. It is like a kiss placed on the hands of a Mother, for the homeland is our earthly Mother.'"

Reston described the Pope's meeting with the Russian-appointed Communist Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski as "perhaps the most striking comparison between officials of church and state in our time. The Pope argued for the freedom and sovereignty of Poland. He never mentioned the Soviet Union, but said Poland had paid for its right to freedom and sovereignty 'with six million of its citizens, who sacrificed their lives on the various warfronts, in the prisons and in the extermination camps.'

"The Polish nation, he added, has confirmed at a very high price ''its right to be the sovereign master that it inherited from the past.''

"This he said in a strong sad voice and was followed by General Jaruzelski, whose speech was delivered with trembling hands, obviously hoping for reconciliation with the Pope on Communist terms, which he did not get," wrote Reston.

"Those who experienced that amazing week report that their lives were forever transformed: for those few days," writes Porter. "An entirely different Poland emerged."

Solidarity marchers (Derzsi Elekes Andor/Wikimedia)

Solidarity marchers (Derzsi Elekes Andor/Wikimedia)

The Solidarity movement surged in popularity. "The Church hierarchy repeatedly urged the clergy not to speak out openly against the regime," notes Porter. "Many priests, however, pushed the limits of obedience by sheltering the opposition and giving anti-Communist sermons. In 1984, one of these priests, Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, was murdered by members of the secret police, and the bond between Catholicism and the opposition was further solidified in the popular imagination.

"By the late 1980s the Church was widely seen as the primary site for anti-Communist activism," writes Porter, "and attendance at mass became more popular than ever before or since. But the old tensions remained, and just beneath the surface the conservative nationalism of many priests was in sharp conflict with the secular liberalism of many of the leading dissidents. Meanwhile, the bishops bemoaned the fact that people were coming to church not to pray, but to express their political resistance to the Communists.

"When the Communist regime extended feelers towards the opposition in the late 1980s, the Church hierarchy was asked to serve as a mediator. The bishops who took part in the Round Table Talks of 1989 insisted that they were not parties to the debates, but neutral guarantors who insured that both Solidarity and the communists were negotiating in good faith.

"This was slightly disingenuous," notes Porter. "It was obvious that their sympathies were with Solidarity -- but it was true that they were committed to ensuring that open conflict (particularly violent

struggle) was avoided at all costs. In this sense, they played a crucial role in ensuring that the voices of moderation and compromise emerged victorious."

A priest blesses Easter baskets in the Polish Święconka tradition (Błażej Benisz/Wikimedia)

A priest blesses Easter baskets in the Polish Święconka tradition (Błażej Benisz/Wikimedia)

Today a majority of Poles, approximately 88 percent identify themselves as Catholic, and 58 percent say they are active practicing believers, according to a survey done by the Centre for Public Opinion Research. According to the Ministry of Foreigns Affairs of the Republic of Poland, 95 percent of Poles are members of a local church. The CIA Factbook gives a lower number – 89.8 percent church members and 75 percent as practicing Christians.

Either number makes Poland one of the most devoutly religious countries in Europe. Polish Catholics participate in church more frequently than their counterparts in most Western European and North American countries. A 2009 study revealed that 80 percent of Poles attend church at least once a year, while 60 percent of the respondents say they do so more often. By contrast, a 2005 study by Georgetown University revealed that only 14 percent of American Catholics take part once a year, with a mere 2 percent doing so more frequently.

Poland, it would seem, is far more Christian than America.

And today it’s not facing the massive, crippling national debt of the rest of Europe – or the United States. It’s not being ripped apart by a wide political divide – Poles know they want nothing to do with socialism or Communism after having it forced on them for 40 years.

And today Poland’s being blessed during a time of economic downturn worldwide.