Waving her diploma over her head, Guadelupe Rojas walked across the stage, shook various university officials’ hands, and laughing took a bow as her family and friends in the bleachers cheered, whistled and applauded.

Her brother, Kiko, who will earn his teaching degree next year, blew a horn that noisily played the first notes of “La Cucaracha.” “Go, Lupe!” yelled her high school history teacher, a retired judge who had recognized her potential when she was a ninth grader – and tried to get her to pursue law as a career. Her grade school’s cafeteria manager stood on a chair, applauding loudly. Her longtime soccer coach blew a referee’s whistle and whooped. His wife blasted a boat air horn.

At the microphone, a dean in cap, gown and academic sashes smiled. “Congratulations, Lupe,” he said. “Best of luck.”

He knew all too well that the young Mexican native will need it. Although Guadelupe graduated from the Honors Program with honors and a double major in physics and math, she faces a grim future. The job market is dismal enough for ordinary college grads; it’s far, far worse for kids here illegally.

Lupe was born near Reynosa, Mexico.

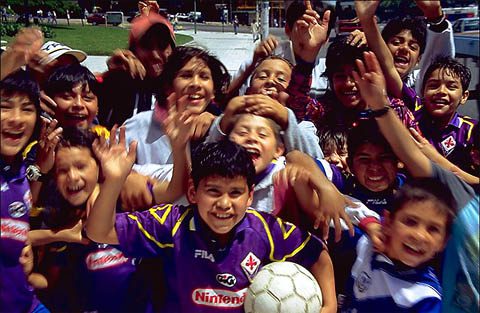

When as a six-year-old, she showed up at her first youth soccer practice, her coach asked where she was from.

“Mexico,” the first grader told him in amazingly good English. Kiko – his real name is Enrique – was four at the time. “My Mommy and Daddy had to wait until nighttime and they waded across the river. But my uncle and my aunt have papers, so they met us at Burger King and drove me and Kiko across. We pretended to be asleep. When the border guards tried to wake us up, we acted like we were sleepy. In English, I kept saying, ‘Are we there yet? Are we there yet?’ like I was dreaming. We fooled him!”

Solemnly, her coach listened. “Lupe,” he said quietly. “That is a great story. Now, you have to promise me that you will never tell it to another Anglo. That story has to be a secret. Do you understand me?”

Soberly, she nodded, her eyes enormous. She never told the story again – to anybody. By the time she was a fifth grader, she and the coach’s daughter, also a fifth grader, were assistant coaches for the local soccer league’s kindergartners. As seventh graders, the two became referees. In eighth grade, Lupe started coaching her own team of third graders.

Although she was a starter on the high school varsity girls’ soccer squad, she earned a full scholarship to the U of A because of her grades, her SAT and ACT scores, her class standing and her years of community service. She had a 4.3 grade point average – the extra .3

points for taking college level classes. She was a member of the National Honor Society, the International Club, the marching band and the school’s volunteer-oriented Beta Club.

Now, as other graduates showed their diplomas to friends and family, she hugged her longtime buddy, the coach’s daughter, who was going to go work for a law firm.

Lupe had no such job prospects. Despite having achieved the highest grades attainable in the Honors Program –all A’s all four years, she is unemployable. Well, not exactly. She works as a waitress in a local Mexican restaurant where Kiko is the dishwasher. They’re both paid in cash – because neither has a Social Security card.

The law says she shouldn’t be here. She should be deported immediately to Mexico.

However, Lupe is as American as anyone. Her Spanish has a discernible Arkie drawl to it. She would be a fish out of water in Mexico. She has no family south of the border, no friends and few memories of her early years there. Her Spanish isn’t even that good.

Shortly after her kindergarten year, her parents split up – and her father took all the family’s papers with him, including birth certificates and passports. Her mother, a hard-working, resilient woman, worked in a local poultry plant using false I.D. and saved up enough money for a down payment on a house – then on two rental houses. But even now she has no permission to be in the United States. They are all illegal aliens, undocumented Mexican nationals living illicitly in the United States.

“I don’t know what to do,” says Lupe. “I’ve got an impressive degree and a nice resume, but I can’t get a job anywhere legally. I can do yard work. Or child care. Or wait tables. If you pay me cash.”

As a high schooler, she tried working at night with her cousin Pasqual at a local industrial laundry – ten-hour shifts washing linens and floor mats for Branson, Missouri, tourist hotels. They were promised minimum wage, but when they got their paycheck, it was half of what it should have been. The laundry owner laughed at them. “Who are you gonna tell?” he sneered. “I know you’re wetbacks. Your fake papers don’t fool me.” For one thing, Pasqual was working as “Hector Figueroa” – the fourth Hector Figueroa who’d worked at the laundry. “Same fake birthday, same fake address,” sneered the owner. ”I know what you are. So, don’t tell me you’ll turn me in. They’ll deport you before they do a thing to me.”

Last year, Pasqual was arrested on a traffic violation and deported when it was discovered he was illegal. Immigration authorities held him in a federal detention center in Louisiana for eight weeks. Last month, he and his Mexican bride slipped across the Arizona border after paying a “coyote” or smuggler of humans several thousand dollars to get them into the United States. She made it to Tucson where she gave birth to a son, who as a result has a U.S. birth certificate and full citizenship. Pasqual, however, got caught wandering in the Arizona desert and is back in Mexico. He’s planning to try to sneak across again next week and is asking friends and

relatives to wire him the money he needs for the new attempt.

Last week, the President of the United States, Barack Obama, threw Lupe a lifeline — but not Pasqual. Days later, the U.S. Supreme Court limited Arizona’s local restrictions — perhaps making it easier if Pasqual tries again. Lupe is filled with hope.

She watched on TV as Obama announced from the White House Rose Garden that “over the next few months, eligible individuals who do not present a risk to national security or public safety will be able to request temporary relief from deportation proceedings and apply for work authorization.”

The work authorization lasts for two years and is available to “eligible individuals,” including those who: came to the United States before their 16th birthday; have not yet reached 30 years of age; have lived in the country continuously for at least five years before the June 15 announcement; are enrolled in school, are high school or college graduates — or have been honorably discharged from the military.

All of that describes Lupe — except the military. She’s ready to apply, but still is a little worried.

Obama’s announcement resembles the “Dream Act,” which Lupe supported enthusiastically on campus. She was hesitant, however, to march in any public demonstrations. The last thing she needed was for her illegal status to become known.

Obama told the press that “it makes no sense to expel talented young people, who, for all intents and purposes, are Americans — they’ve been raised as Americans; understand themselves to be part of this country — to expel these young people who want to staff our labs, or start new businesses, or defend our country simply because of the actions of their parents — or because of the inaction of politicians.”

“I am excited,” says Lupe – which is not her real name. Nor is “Kiko” her brother’s name. They are both still afraid that they’ll be deported if they don’t do the paperwork right and in time. They have a friend whose application was rejected because his birth certificate had torn and was held together with tape. She declined to have her picture used for this article, either, although this story is being written by a longtime friend who announced her high school soccer games from the press box.

Lupe is quietly hopeful, but admittedly fearful. So are thousands just like her. For two decades, kids have attended America’s schools and gone through U.S. colleges without permission to be in the country. They’ve gotten good educations. And they consider themselves Americans. Many are conflicted — upset that some Americans reject them as aliens, yet fiercely loyal to the land whose flag they’ve pledged allegience to every day at school.

They’d like the issue of their future resolved.

“While not exactly a permanent measure,” writes Dr. Jill Rooney, “Obama’s decision does grant at least temporary relief to thousands of students facing imminent deportation. For these students, brought here by their parents when they were children, deportation would mean the end of their education. Many of whom have done their best to work hard, attend school, and contribute to society.

“This new measure helps them continue their education in the land they know as home. In addition, not all who fit this category will be eligible; those who cannot take advantage of the immigration initiative include those with ‘significant misdemeanors’ on their records.”

That apparently won’t include Pasqual – although he was only arrested on a minor traffic offense. He’s broken federal law by trying to sneak back into the country. It remains to be seen whether his offenses constitute “significant misdemeanors.”

There is wariness in Lupe’s eyes as she talks about Obama’s act. It seems a little vague. And it’s only a two-year reprieve. If Lupe takes advantage of it, when it lapses in two years, will she be automatically deported? For years she had stayed off immigration officials’ radar. She’s a non-person. Will she regret registering for Obama’s reprieve in two years?

Indeed, the new regulation is only a “deferral of the process,” said University of Georgia professor Betina Kaplan in an interview with National Public Radio.

Observer Joseph Nevins wonders in the Huffington Post whether the age limits will exclude too many. Critics on the left say Obama has not done enough. Critics on the right complain that Obama is threatening American jobs and condoning those who flaunt the law.

Guadelupe is grateful. She says Obama has her vote. Unfortunately, she’s years away from being able to vote in any U.S. election – assuming that this is putting her onto a path toward citizenship in the only country she knows.

But she knows that she doesn’t want to be forced to return to Mexico.

America is her home.