In September of 1998, life was not exactly going the way I'd planned. Work and love, two of the big pillars of life, had shifted, and I was feeling just a little wobbly. The previous May, taking a hard look at my savings and a big leap of faith, I'd left a job I hated to work on my very first book proposal. After 16 weeks of work and at least as many rewrites, 60 pages were gone, submitted to publishers. Sure, I was excited, but I'd made one little mistake: Without the proposal to work on, I hadn't thought about what to do while I waited for an answer. And who knew how long that would take? Or what the answer would be?

I was also struggling with a failing romance. My relationship with my fiancé was feeling like a long-distance romance, and I don't mean geographically. The Hollywood ending I'd been hoping for was starting to seem scripted more by Kurosawa than Capra. I needed to do something that felt definite: I wanted to prove to myself that I still had some small measure of control over my life. So I got on the internet and started looking up apartment rentals in Italy.

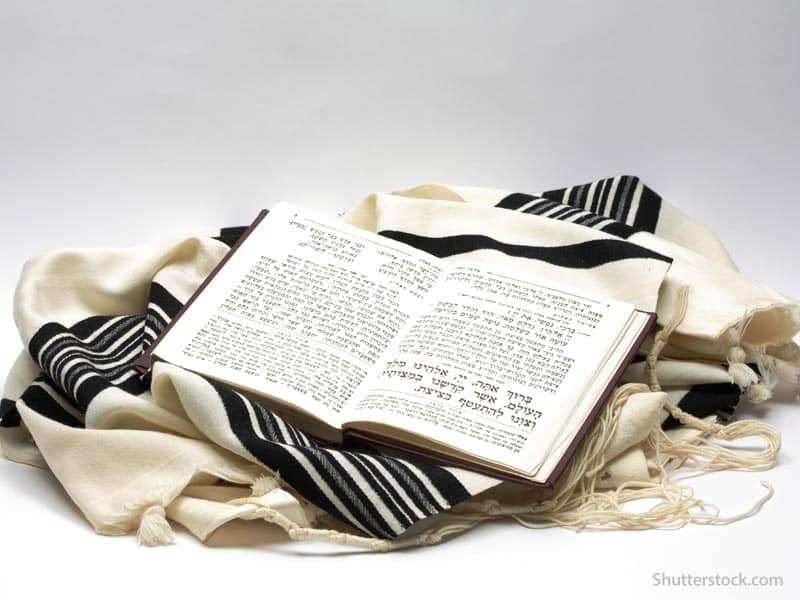

That is how it happened that I found myself in Florence for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It was the first time in a number of years that I would be away from my New York community of friends, and my synagogue, for the New Year. I thought about observing the holidays at the beautiful Moorish-style Tempio Israelitico in Via Luigi Carlo Farini, but the one Friday-evening Shabbat service I attended was a little sad, a little lonely: It wasn't a place I wanted to be for the holidays known, with reason, as the Days of Awe.

I decided that I'd be happy simply to observe taschlikh, the time when Jews symbolically empty their pockets of sins, of sorrow, of poor intentions. The word tasche, in German, means "pocket"; taschlikh literally means "of the pockets." The custom began in Europe about 800 years ago, and the simple outlines haven't changed much. You simply stand above or beside a moving body of water--a brook, a river, an ocean--and if you choose, say some simple prayers. And you symbolically empty your pockets of sins, disguised as breadcrumbs, and scatter those crumbs on the moving water. Even in its simple outlines, the ritual echoes the great themes of repentance and renewal that reverberate throughout the Days of Awe. How do breadcrumbs help balance out our sins? George Robinson, author of "Essential Judaism," notes that the word for "sin" in Hebrew is kheit, a term derived from archery, which refers to a shot that falls short of its mark. "Hence," he writes, "those sins that we repent at this time of year are a failure to live up to our potential, a failure to fulfill one's obligations." During the High Holy Days, we not only repent our sins, but vow to do better, to try to make the arrow hit its mark more certainly in days to come.

| _Related Features | |

|

|

|

The Upper West Side of Manhattan, where I live, is said to have the greatest population of Jews outside of Israel. In the afternoon of the first day of Rosh Hashanah, a great wave of people make their way to the western edge of Manhattan island, crossing curving Riverside Drive, following one of the sloping paths through the green band of Riverside Park, through one of the tunnels under the Henry Hudson Parkway, and emerging down on the narrow strip of asphalt that lies just a few feet above the Hudson River. Clustering together, groups of people stroll, chat, and pause at the metal railings lining the path to say some words of prayer and scatter breadcrumbs in the moving waters of the Hudson.

Instead, on this day, I turned alone down the crooked streets to the jade-green Arno. I'd walked halfway across one of the many bridges spanning the small river when I realized I didn't have any bread with me. Oh well, I thought. Too late now.

I leaned against the balustrade, my weight against the reassuring stone, the sun warming my back. In a way, it seemed fitting that I had no breadcrumbs in my pockets. Like everything else about this particular time in my life, the observance could unfold spontaneously, without the comfort of familiarity.

I watched the water sluice over the concrete feet of the bridge. And then I noticed that I had company. A little boy, maybe 6 or 7, with hair the color of lemon sorbetto, began walking across the bridge. He was with his family: two parents and a little sister. He hung back from them and took up a place by the rail. Like me, he watched the water. His family stood in the middle of the road, in the middle of the small bridge, the adults chatting quietly. Waiting for him to run and rejoin them. The boy reached into a paper sack he was holding. His hand re-emerged holding crumbs of bread; he threw the crumbs into the water. The Lord provides, I thought.

They swirled for a moment above a school of fish, little fellows, gray and slithery, playing where a cascade of water formed a little waterfall. Bread and fishes seemed appropriate for Catholic Italy, after all, and I enjoyed the way the ritual had been translated. The little boy had thrown my sins into the water for me, the stale bread of my sins. Not too many, but there, ready to float away.

We waited, the boy and I, as the crumbs lingered on top of the water at the foot of the bridge. The fish did not rise to devour them as I expected, and as I imagine the boy intended.

Finally, the boy turned away. I stayed and watched the crumbs float downstream.

It was just a few days later that I got word that a publisher had bought my book proposal. I shared the news with my fiancé by phone; in the same conversation we both acknowledged that our troubled romance had to end. Somehow, that special taschlikh had cleared my thoughts. It reminded me that life is a broad, clear stream that continues to flow through whirlpools, waterfalls, and long slow currents. Where the last small remains of a loaf of bread can float peacefully out of sight. And that even if I don't always have my own bread to throw on the waters, the Lord provides if I at least get myself to the edge of the river. A few days after that, I thought to check the map, to find out the name of the bridge. It was called the Ponte delle Grazie: the Bridge of Thanks.

| _Related Features | |

|

|

|