Then I woke up and it came back to me. That the guy, supposedly my boyfriend, who came out with me to this joint, a fleabag in Waikiki, was now gone, run off with a chick on her way to Fiji, and he--actually they--had left me with the hotel bill, which since I had no idea how to pay I was avoiding by just staying in the hotel and not checking out. But you know, the vision I had before, when I was just half awake, that was the important part. That was like the angels talking, when they speak to you and teach you right before you're born, and then they put their fingers on your lips--Sh! don't tell! You almost forget, but somewhere inside, you remember.

At the time, that morning, I just lay there and had no idea what to do, not to mention I had never as far as I knew even believed in the existence of God. But in my subconscious, and my unconscious, and everywhere else, I had all these questions and ideas about this higher power and this divine spirit, and maybe I would have been dealing with them if I hadn't been so broke.

Finally I got up. I sat on the edge of the queen-size hotel bed. The bedspread was halfway off, sliding onto the floor, and the spread was green, printed yellow and orange with bird-of-paradise flowers so enormous they looked like some kind of dinosaur parts. The headboard was white rattan. So was the dresser and the mirror frame and the desk. There was no chair. Everything that could be nailed down was.

There I was all by myself, yet it wasn't exactly like I'd had some kind of one-night stand! We were folk dancers. That's how my boyfriend and I had met a couple of years before. Gary and I were two of the original dancers that danced in Cambridge at MIT. Balkan on Tuesdays. Israeli on Wednesdays. This was in the seventies when the folk scene in Boston was just starting, and there was a group of us--it was our life. We'd gather together at night--guys in cutoff shorts and girls in Indian gauze skirts, tank tops. In winter we'd strip down out of our parkas and ski hats and wool socks, and unzip until we were barefoot. I had long straight hair, light brown, and I wore it loose down to my waist, and I lived to dance in Walker Gym with my hair flying around me and my shirt against my bare skin, and the smooth gym varnish on the floor like syrup to my toes.

The music came from a tape recorder mounted on a little wooden cart painted gypsy colors, yellow and red, and stenciled in fancy green: MIT FOLK DANCE CLUB. The names of the dances were scribbled in chalk on a green chalkboard wheeled in from one of the classrooms. Then, from seven to eleven at night, we circled and wheeled and flew. We would dance like this for Balkan: twenty at a time together with our arms linked in a line, and our legs kicking and feet moving to rhythms like 7/8 or 11/16. Like this for Israeli: in concentric circles, feet flying, every other person off the ground.

Originally he was the one with the traveling bug. Gary was one of those Vietnam-era graduate students, thirty-five at that time, which was '74. He was still working on a government public health grant at Harvard, and he used to cart around boxes of those manila computer punch cards. Every once in a while the profs would fire up the old computer, and they'd input their data with a clicking and a clacking till the oracle spoke, spewing out numbers on that wide paper with pale-green and white stripes.

Then Gary and the other grad students would all go back to their shared offices adorned with shag carpet remnants and cork bulletin boards, and they'd ponder the numbers. Gary had been doing this for years; and since it was a longitudinal study, which meant it didn't ever end, he was getting kind of restless. But I, on the other hand, was really busy, since I was just 20--in the middle of stopping out of college and getting seriously into dancing and my music--folk stuff on my guitar. I listened to Joni Mitchell and Carole King and Jackson Browne. And of course I was writing my own stuff, too, all in their same styles. I was biking over the BU Bridge to Central Square, where I was working for this antiwar, antinuclear couple, Vivica and Dan, who I'd met from dancing, and who had originally come from Berkeley. We were holed up, the three of us, in a little one-room office trying to put a stop to military spending. To me bringing peace about was pretty good. But Gary, being fifteen years older, had bigger ambitions for the planet. He started talking about how he wanted to go west.

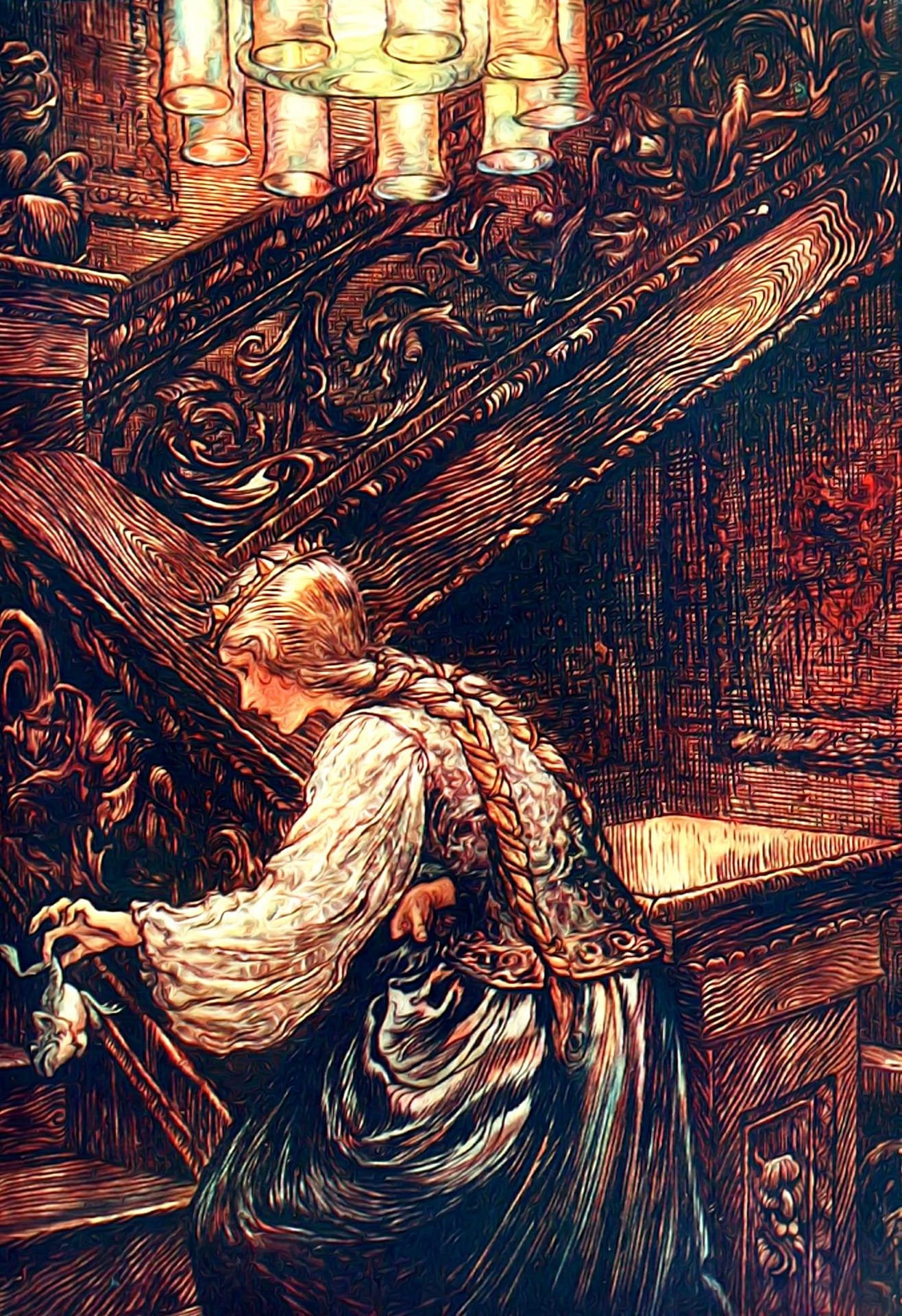

The thing was I loved him. Not that he had a face to sink a thousand ships. He had fair skin, blinky brown eyes, shoulder-length hair, a Fu Manchu moustache. But he had beautiful feet, elastic arches. He had the longest arms of anyone I knew. And when he jumped! He could have been a pro. He could have traveled the world leaping in the air. That's the way I pictured it, him leaping and me spinning at his side. I still hadn't gotten over it, being so much younger than he was, and him choosing me to be his partner--because my dancing was so good. And getting to live with him, which meant getting out of my dad's house and my stepmother's hair. And just realizing that Gary thought I was beautiful! It wasn't like I was plain. I wasn't plain at all. I was slender and had big black eyes, sleepy with eyeliner, and that shimmery loose hair, so when I danced I looked like a ballerina down at the hem.

But I was young--not even one-and-twenty like the guy in the poem--and I couldn't believe Gary with his long arms and his gorgeous feet and hard muscles in his calves actually thought that I was beautiful.