There was a time when it seemed a woman with breast cancer underwent a “radical mastectomy,” the full removal of the mammary glands, lymph nodes and pectoral muscles. A disfiguring procedure, it was dreaded – and even declined by some women, such as French movie star Brigitte Bardot, who considered dying of the disease rather than being “less a woman.”

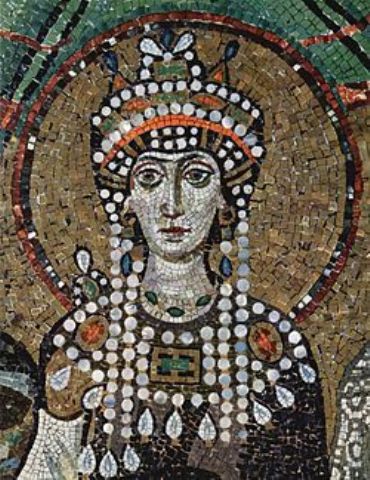

The first recorded mastectomy for breast cancer was performed around 548 AD, when it was proposed by the court physician Aëtius of Amida to Theodora, the wife of Emperor Justinian I, considered by some to be the most influential and powerful woman in the Roman Empire’s history. Some sources even mention her as empress regnant with Justinian as her co-regent. She declined the surgery and died a few months later.

Theodora

Fortunately, science has advanced and according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the procedure is increasingly rare. The study was led by Monica Morrow, M.D., chief of the Breast Service in the Department of Surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, along with Steven Katz, M.D., M.P.H., and colleagues at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

They found that during a nine-month period, a group of 1,984 women aged 20 to 79 years with stage 1 and 2 breast cancer experienced the following:

67 percent of women reported that their first surgeon recommended breast-conserving surgery and that they had successful procedures

13 percent had mastectomies after initial surgical recommendation

8.8 percent had mastectomies when there was no clear surgical recommendation for either procedure

8.8 percent reported having unsuccessful breast-conserving surgery that required revision with mastectomy.

This is a far cry from the days when a full breast removal was the only thing the doctor would recommend.

The study concluded that, surprisingly, many women choose a mastectomy, “especially in the absence of a surgeon recommendation favoring one procedure over another.

“This is consistent with previous studies performed by these investigators that have shown that when both procedures are medically appropriate, increased patient involvement in breast surgery decisions is associated with greater probability of mastectomy,” reported Morrow and Katz.

“In this study, one-third of patients appear to choose mastectomy as initial treatment when not given a specific recommendation for mastectomy by their surgeons. Researchers speculate that patients may prefer mastectomy for ‘peace of mind’ or to avoid radiation and are often strongly influenced by concerns about disease recurrence and fear.

“Women need to understand that although it intuitively seems obvious that a bigger surgery is a better surgery, it may not be the case,” noted the study. “There are some patients for whom mastectomy is the best medical treatment.”

However, “women need to make sure that if they are choosing mastectomy,”that they understand it is not going to improve the likelihood of breast cancer survival,” wrote Morrow and Katz.

“Our results and those from other studies we performed suggest that surgeons face special challenges in how they discuss treatment options and elicit the treatment preferences of their patients with breast cancer. Our results reinforce that both patient preferences and surgeon recommendations are powerful determinants of treatment,” said Katz, who is a professor of internal medicine and health management and policy at the University of Michigan.

“This study suggests that breast-conserving surgery has been appropriately adopted by surgeons and for most women — if they are given a specific reason why they are not a good candidate for breast-conserving surgery — a second opinion is not likely to change that,” Morrow says.