Let me define historical Jesus studies as the attempt to get behind the canonical Gospels to discover what the real Jesus was like. Inherent to the historical Jesus discipline is the belief that the canonical Gospels and the Church got Jesus wrong or are biased — or should I say that the Church believes too much about Jesus and that the real Jesus was less than the Church’s Christ. In other words, historical Jesus studies attempt to construct an image of Jesus in distinction from the canonical Gospels and the Church’s beliefs.

Let me define historical Jesus studies as the attempt to get behind the canonical Gospels to discover what the real Jesus was like. Inherent to the historical Jesus discipline is the belief that the canonical Gospels and the Church got Jesus wrong or are biased — or should I say that the Church believes too much about Jesus and that the real Jesus was less than the Church’s Christ. In other words, historical Jesus studies attempt to construct an image of Jesus in distinction from the canonical Gospels and the Church’s beliefs.

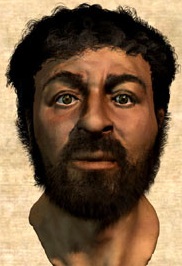

Example: Is that what you think Jesus looks like? This is what a BBC program sketched for what a 1st Century Jewish male looked like. The jolt of this image with your image is what historical Jesus studies attempt to do.

I participated in this discussion for the better part of 15 years. Much fruit has come of historical Jesus studies, most notably the sharper profile of Jesus in his Jewish context. But the enterprise makes no sense until we see it as the attempt to construct an image of Jesus more accurate than what we find in the Gospels.

Let me say this one more way: Yes, historical Jesus studies try to get back to what Jesus was really like but involved in that is the belief that the real Jesus and the canonical Gospel Jesus are not the same. I know some conservatives conclude that virtually everything is authentic and conclude that the canonical Gospel Jesus is the same as the historical Jesus. But I don’t think such studies really are historical Jesus studies. Critique of the Church’s belief about Jesus is inherent to historical Jesus studies.

This introduces what I think is the most significant, even if thoroughly skeptical, study on the historical Jesus discipline in the last fifty years: Dale Allison’s new book The Historical Christ and the Theological Jesus

. There’s a melancholy to this volume, almost a looking back at the hopes of a former era when some thought they’d find the real Jesus behind the Gospels, and that melancholy comes into words with this: “I do not long for that old-time religion, nor do I wish to believe in my own belief but, as quaint as this may sound to some, I want to know the truth, even if I cannot cheer it” (4).

The book therefore is Allison’s “personal testimony to doubt seeking understanding.” He’s skeptical we have tools that let us get back to what Jesus was like behind the Gospels. “When we read [the Gospels], we should think not that Jesus said this or did that but rather: Jesus did things like this, and he said things like that” (66).

I like this book, not because I agree with Allison’s own conclusions about specifics, but because I came to some similar conclusions when I wrote Jesus and His Death. When I was done I wrote an introductory chp that sketches historical method and I concluded that the historical Jesus has very little use for the Church and that, essentially, we face a choice: we either believe the Church’s construal (the Gospels Jesus) or we make up a Jesus for ourselves with the methods that cannot prove certainty. The historical method can only do so much — and I tried my best in that book — and the one thing it cannot do is get us back to a Jesus before the Gospels. Every construction always looks like the one who writes the history.

A dark cloud looms over the attempt; the attempt is worth it, Allison thinks. We don’t know he seems to be saying, and he doesn’t mind the ambiguity. Historical Jesus studies has light to shed, and more light to shed, but the conclusions are not terribly encouraging — that’s how I read Allison.

Allison’s book brings the quest for the historical Jesus to a new dead-end. We can’t do what we thought we were going to do. The Third Quest is, at least for me, officially over. Questions remain; passions for historical probings still remain — but Allison’s book is the new fiery brook over which each scholar must cross.